Geo-blocking as a tool to prevent being sued in EU Member States for cross-border copyright infringements?

Because of the internet and globalization, copyright infringements often have a cross-border character. If you post a blog illustrated by an image which you found on internet, you can be sued by the copyright holder of the image before the courts in all 27 EU Member States. This blog post focuses on geo-blocking as a tool to prevent being sued in Member States for cross-border copyright infringements. The latter topic will be viewed from various legal perspectives namely private international law, copyright law, EU law, in particular the Geo-blocking Regulation, the right to information, freedom of expression and cross-border trade.

Main points:

- In view of the CJEU’s accessibility approach to jurisdiction for online copyright infringements, geo-blocking could be considered as a tool to prevent being sued before courts of multiple EU Member States.

- In spite of the Geo-blocking Regulation, geo-blocking can be used as a tool to reduce the risk of being sued in particular or multiple EU Member States for cross-border copyright infringements with respect to audiovisual services; electronically supplied services that contain copyright protected content; and online non-commercial content and services.

- Adopting the ‘directed activities’ approach to jurisdiction for cross-border copyright infringements would provide predictability and therefore decreases the need to use geo-blocking which is beneficial for the flow of online information, freedom of speech, and cross-border trade.

Broad approach to jurisdiction regarding cross-border copyright infringements

To determine whether the court of an EU Member State has jurisdiction regarding a cross-border copyright infringement case, the EU Private International Law instrument Brussels Ibis Regulation has to be applied. According to the main jurisdiction rule in Article 4 Brussels Ibis, the courts of the Member State in which the alleged copyright infringer is domiciled have jurisdiction regarding the entire cross-border copyright infringement dispute. In addition, based on Article 7(2) Brussels Ibis related to tort claims, the alleged copyright infringer can be sued before the courts of the place in the Member State in which the harmful event occurred or may occur. In the rulings Pinckney, Hi Hotel, Pez Hejduk, the CJEU broadly interpreted Article 7(2) Brussels Ibis: the courts of a Member State have jurisdiction based on the mere likelihood that damage caused by the alleged copyright infringement occurs in that Member State. The jurisdiction of the latter court will be limited to the territory of the Member State of that court. The rulings Pinckney and Hi Hotel demonstrate that the court of a Member State can even obtain jurisdiction if another person, known as a third party, put the copyright infringing content online or products for sale in that Member State regardless of whether the defendant has been aware of it. Particularly in case of ubiquitous copyright infringements, the CJEU’s broad approach to jurisdiction may lead to forum shopping; the copyright holder can file the copyright infringement claim before the courts of various Member States. The alleged copyright infringer can therefore unpredictably be sued before the courts of multiple Member States based on the mere online accessibility, or availability, of copyright infringing content or products in these Member States. In view of the paramount principle of predictability, this broad approach to jurisdiction regarding cross-border copyright infringements has been criticized by several scholars like the author of this blog (see paragraph 5.2.4.1 of the dissertation ‘Jurisdiction in Cross-border Copyright Infringement Cases: Rethinking the Approach of the Court of Justice of the European Union’).

Factors that contribute to ‘forum preventing’

Several factors may play a role in preventing to be sued in certain Member States for cross-border copyright infringements. From a perspective of the copyright holder, the following factors can contribute to the decision where to forum shop. First, the factor of geographical distance, it will not be desirable to be sued far away from the Member State where one is domiciled since it will be costly and time consuming. The usual length of the court proceedings in a Member State could be another factor to take into account. In view of the positive outcome of the case, it can be relevant to consider the national procedural law such as which party has the burden of proof. The existence of a territorial limited copyright license agreement could also be a factor. For instance, a licensee, like an online music provider, may on the basis of a copyright license agreement not be allowed to use copyrighted work, as music albums, in certain Member States.

In view of the territorial protection of copyrights, it is also important which national copyright law will be applied to the cross-border copyright infringement case. Although there are several international treaties related to copyrights, such as the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, there exists no universal unified copyright law. As stated by the conflict-of-laws rule for infringement of intellectual property rights in Article 8(1) Rome II Regulation, the competent court has to apply the copyright law of the state for which protection is claimed, lex loci protectionis. The court of a Member State that has jurisdiction on the basis of Article 7(2) Brussels Ibis will generally apply the national copyright law of that Member State. In spite of the vast amount of EU copyright legislation, copyright law has not yet been fully harmonized within the European Union. For instance, the protection of moral rights related to copyrights varies between the national copyright laws of the Member States. The protection of copyrights can be expired in certain Member States as illustrated by the case related to copyrights on Anne Frank’s diaries. Furthermore, it is better to prevent being sued before a German court since German law states that if a copyright infringement has been intentional it even constitutes a criminal offence which is subject to a fine or imprisonment.

Can geo-blocking be used as a tool to prevent being sued in EU Member States?

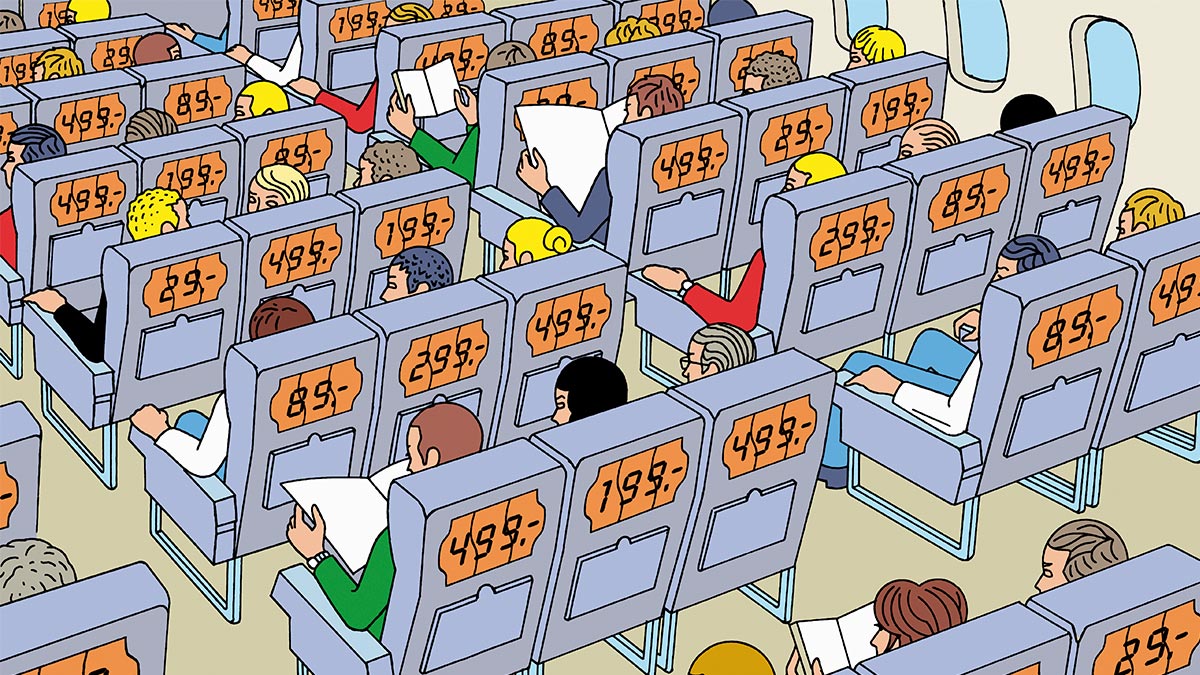

In view of the accessibility approach to jurisdiction and the factors mentioned above, geo-blocking can be considered as a tool to prevent being sued in specific Member States for cross-border copyright infringements. Geo-blocking is a technology that disables access to, or use specific features of, online interfaces, such as websites or apps, based on the internet user’s geographic location. This location can generally be identified through the user’s IP address. For instance, you can use geo-blocking to disable access to your blog for internet users of particular Member States. However, as mentioned earlier, it may still be possible to be sued in these Member States in case your alleged copyright infringing blog has been copied and put online by a third party. Moreover, you can always be sued before the court of the Member State where you are domiciled. Yet, geo-blocking will nonetheless reduce the risk that you may be sued in particular or multiple Member States. Not-for-profit providers of online information, such as open access scientific repositories and online encyclopedias, can use geo-blocking as a tool to reduce the risk of being sued in multiple EU Member States for copyright infringements. However, geo-blocking will negatively affect the cross-border flow of online information which is in particular important for education and innovation.

As a part of the EU Digital Single Market Strategy, Article 3 of the Geo-blocking Regulation prohibits a trader to use unjustified technological measures that block or limit a customer’s access to the trader’s online interface for reasons related to the customers’ nationality, place of residence or place of establishment within the EU. The Geo-blocking Regulation broadly defines a trader as any natural or legal person, even residing or established outside the EU, who is acting, including through any other person, in the EU for purposes relating to the trade, business, craft or profession of the trader. The concept of customer has also broadly been defined as a natural person who is a national of, or resides in, a Member State, or an undertaking which has its place of establishment in a Member State, and receives a service or purchases a good within the EU for the sole purpose of end use. For instance, a small bookshop that sells second-hand books online is prohibited to geo-block its website for customers of specific Member States. To prevent being sued in multiple Member States for alleged copyright infringements, particularly small trading companies may not prefer to offer their goods online to customers in the EU. The latter will not facilitate the internal market and cross-border trade.

However, the Geo-blocking Regulation does not affect services referred to in Article 2(2) of the Services Directive such as audiovisual services, for instance, streaming of videos and broadcasting. Video streaming services, such as Netflix, are therefore allowed to block access to audiovisual services for customers of particular Member States which will prevent being sued in these Member States for cross-border copyright infringements. While the geo-blocking of audiovisual content can be considered to enhance copyright protection, it may nonetheless increase online piracy as pointed out by Giuseppe Mazziotti. Presuming that social media platforms, like Twitter and Facebook, are traders and its users can be considered as customers under the Geo-blocking Regulation, they are allowed to geo-block or limit access to audiovisual services such as a livestream. Particularly in view of the liability of online content sharing service providers for giving public access to copyrighted-protected works, as laid down in Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, these platforms can attempt by means of geo-blocking to avoid being sued in multiple Member States for cross-border copyright infringements. Geo-blocking access to social media will nonetheless impede the cross-border exchange of views which has a detrimental effect on the right to freedom of expression and information.

According to Article 4(1)(b) Geo-blocking Regulation, traders can apply discriminatory general conditions to access non-audiovisual electronically supplied services the main feature of which is the provision of access to and use of copyright protected works such as music, audiobooks, e-books, games, or software. For instance, digital music providers or music streaming services, like Spotify, can employ different prices for customers of different Member States. Although these traders are not allowed to block or limit access to their online interfaces due to Article 3 Geo-blocking Regulation, they can thus apply different conditions on the basis of the customer’s place of residence, or nationality, when providing access to their electronically supplied services that contain copyright protected content. Particularly in view of territorially limited copyright licenses, the latter traders may not provide access to particular services for customers in certain Member States to prevent being sued in these Member States for copyright infringement.

In short, geo-blocking can be used as a tool to reduce the risk of being sued in multiple Member States for cross-border copyright infringements with respect to audiovisual services; non-audiovisual electronically supplied services that contain copyright protected content; and online non-commercial content and services. However, as explained above, geo-blocking can have a negative impact on the flow of online information, freedom of speech, cross-border online transactions and it may decrease copyright protection due to online piracy. While the review of the Geo-blocking Regulation should assess whether the prohibition to geo-block can be extended to audiovisual services and electronically supplied services that contain copyright protected content, it is questionable whether this extension can be achieved. As pointed out by several researchers, the territorial protection of copyrights and financial importance of territorial licensing of audiovisual works for the film industry will likely work against the extension of the Geo-blocking Regulation to audiovisual works.

‘Directed activities’ approach to jurisdiction will provide predictability and keep the internet more open

The author of this blog advocates in her dissertation (chapter 8) to replace the ‘likelihood of damage’, or accessibility approach to jurisdiction by the ‘directed activities’ approach to jurisdiction under Article 7(2) Brussels Ibis for cross-border copyright infringements. With respect to ubiquitous copyright infringements, full jurisdiction should be provided to the courts of the Member State in which the alleged damage has clearly been substantial in relation to the entire damage. The proposed approach to jurisdiction will provide predictability to potential copyright infringers as regards in which Member State they may be sued since it requires that the defendant intended to direct copyright infringing activities to the Member State of the court seised. With respect to online activities, relevant factors that indicate ‘directed activities’ are, for instance, the use of a specific language, a country code top-level domain, or restricting the delivery of goods and services to a particular Member State.

Compared to the ‘likelihood of damage’, or accessibility approach to jurisdiction, the ‘directed activities’ approach will provide more predictability to potential copyright infringers as regards in which Member State or Member States they may be sued. While the Geo-blocking Regulation has generally reduced the traders’ tools to prevent directing activities to a particular Member State, namely the use of geo-blocking and discriminatory conditions, traders are nonetheless allowed to use the factors as mentioned above. For instance, an online seller can indicate its intention to direct activities to a specific Member State by using the language of that Member State or providing only delivery of goods in the specific Member State. Since the ‘directed activities’ approach will provide predictability as to in which Member State you may be sued, it decreases the need to use geo-blocking. Hence, it will likely keep the internet more open which is beneficial for the flow of online information, freedom of speech, and cross-border trade.

| This guest blog was written by Birgit van Houtert for the IGIR and METRO Faculty of Law Maastricht #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022 project - More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

This guest blog is part of the project #COMIPinDigiMarkts2022. These blogs have been specially prepared by participating internal and external project members and focus on competition law and IP law, with particular reference to the digital markets.

Also read

-

In its fining decision of 14 September 2021 regarding Samsung, the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) imposed a fine of over EUR 39 mln on Sa

-

Digital platforms are one of the key developments in facilitating industry 4.0 and are at the center of the multifold benefits the consumers derived through this. An important feature of the digital platforms is the presence of high sunk costs and low marginal costs (UNCTAD, 2019).

-

Digitalization has gradually changed business models and reshaped human lifestyles.