Pledge first, Think Later! How Giving Pledges Increase Donations to Cost-Effective Charities

In 2023, private donations in the US surpassed $500 billion for the first time, exceeding the total amount of official development assistance disbursed by all members of the OECD combined by more than double (Giving USA Foundation, 2021). These figures, alongside recent advances in development economics that revealed substantial differences in cost-effectiveness across interventions, highlight the immense potential of private charitable contributions and the importance of donors' charity choice in improving the welfare of the global poor. Years of research in development economics, including the Nobel-prize-winning work of Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer, has provided reliable insights into the most cost-effective strategies for combating extreme poverty. Their experimental approach has become the foundation for scientific charity evaluation, allowing private donors to identify the organizations and interventions that have the greatest impact per dollar donated on the causes they care about.

For example, deworming pills are roughly 100 times more cost-effective in increasing school attendance in Sub-Saharan Africa than scholarships or school uniforms., Yet, most private donors do not consider this information when making their donation decisions (Fong & Oberholzer-Gee, 2011; Metzger & Günther, 2019). Consequently, resources continue to be allocated toward interventions with marginal or unknown effectiveness (MacAskill, 2015; Singer, 2009, 2015).

Thus, we need to understand the factors that explain why most donors do not adopt a Utilitarian stance on charitable giving and maximize the per-dollar impact of their donations. Existing literature provides two main explanations: (1) the preference-based explanation, which acknowledges that many donors have subjective preferences for charitable giving or seek emotional rewards instead of supporting the most cost-effective interventions (Andreoni, 1990; Berman et al., 2018), and (2) the belief-based explanation suggesting that donors frequently make errors in assessing cost-effectiveness due to a lack of knowledge and common misconceptions, leading to suboptimal decisions (Caviola et al., 2014, 2020; Oppenheimer & Olivola, 2011).

Building on the belief-based explanation, we propose that attention is a crucial constraint for effective giving. Previous experiments have demonstrated that donating to charity requires time, effort and attention (Castillo et al., 2023). It involves searching for and reviewing information about the potential charity, experiencing psychological distress when deciding whether or not to donate and how much to give, and taking the time to complete the transaction (Castillo et al., 2023; Dickert et al., 2011; Hutchinson-Quillian et al., 2021). Throughout these steps, donors must maintain a high level of attention. Multiple attention-based choice models in economics predict that individuals' limited attention capacity can impact decision quality, particularly in tasks requiring mental effort (Bordalo et al., 2013, 2016, 2020; Gabaix, 2014; Kőszegi & Szeidl, 2012). Consequently, the literature finds that a lack of attention and distractions cause donors to underweight their altruistic motives, leading to reduced donation rates (Andreoni et al., 2017; Chao, 2017; Exley & Kessler, 2019; Exley & Petrie, 2018; Momsen & Ohndorf, 2023).

We investigate the potential of giving pledges to reduce the complexity of donation decisions and, consequently, improve decision quality. Almost all charities accept some form of pledge, such as recurring donations, contributions during National Public Radio fund drives, as well as planned donations like bequests, long-term commitments to donor-advised funds, and announcements on pledge platforms such as the Giving Pledge, Giving What We Can, and Founders Pledge (Andreoni & Serra-Garcia, 2021a). We hypothesize that giving pledges, which require planning but do not commit donors to a specific charity, reduce spontaneous giving and allow donors to focus more on available ratings and information when deciding where to allocate their promised donations. In particular, we propose that planned giving through pledges simplifies donation decisions by breaking them down into two steps: (1) the amount choice when pledging and (2) the charity choice when fulfilling the pledge by allocating the promised amount to potential charities. This allows donors to focus more attention on evaluating charities, particularly their cost-effectiveness. As a result, we expect this mechanism to influence charity choices in favor of more cost-effective options.

Moreover, we posit that the hurdle to pledge is lower than to donate, as making a pledge requires no effort related to transacting funds or reviewing detailed information about charitable options. Experimental research shows that self-image concerns, guilt aversion, and a desire for consistency lead individuals to uphold their promises, even when made anonymously (Andreoni & Serra-Garcia, 2021a; Charness & Dufwenberg, 2006; Tonin & Vlassopoulos, 2013; Vanberg, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesize that providing donors with the option to pledge increases the donation rate and, consequently, overall generosity.

Experimental Design

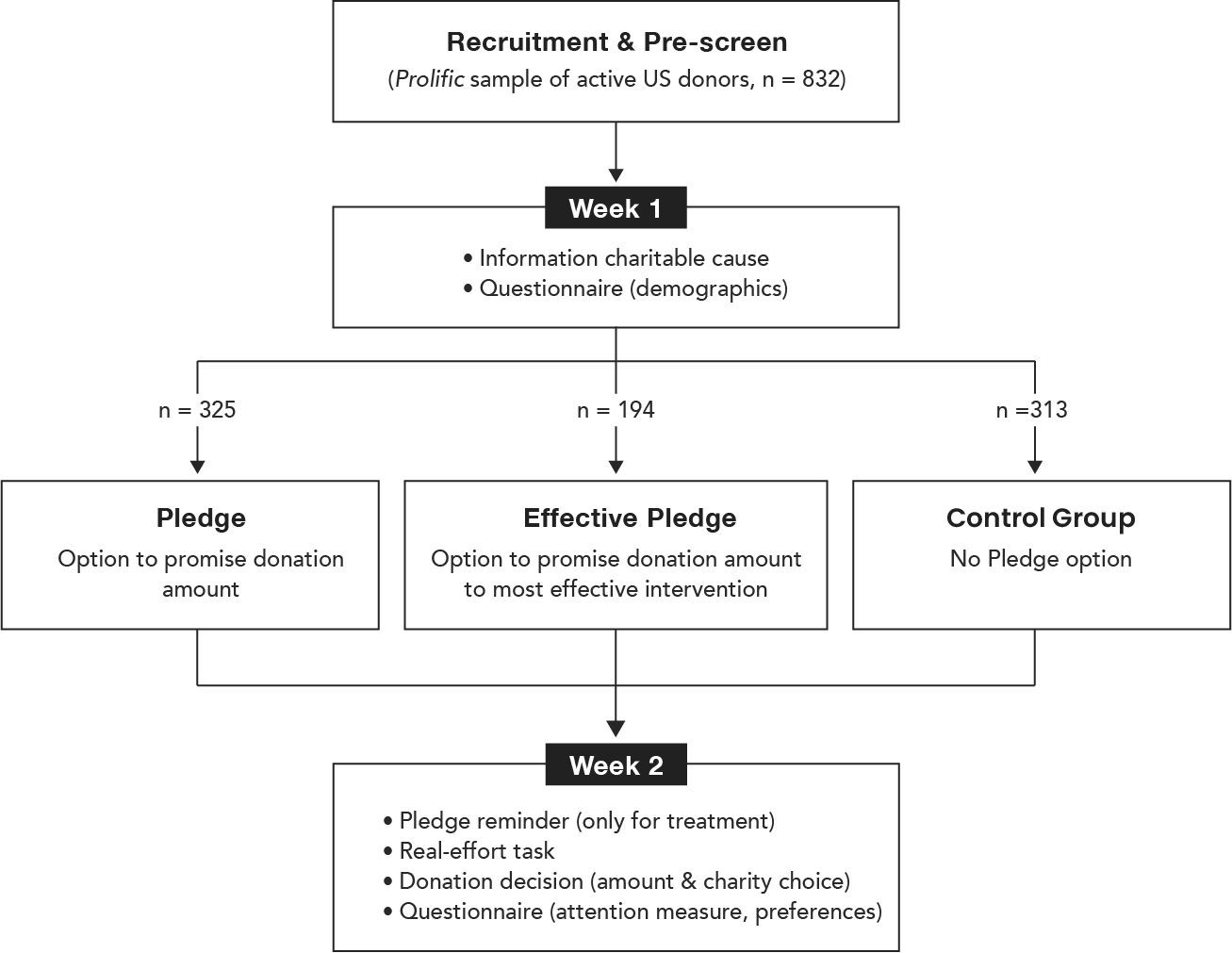

We test these hypotheses in an online experiment on Prolific researching active donors in the United States (n = 832). In the first session of our experiment, all participants were presented with two charities addressing the issue of school absenteeism among pupils in Kenya: one organization offered scholarships, while the other administered school-wide deworming treatments. All participants were informed that they could donate to either or both charities in the second session. However, only the treatment group had the opportunity to pledge a donation without committing to how they would allocate this amount between the two organizations at that point. One week later, all participants returned to the second session of the experiment to make their ultimate donation decision. At this time, they were informed that, on average, each £ donated to fund deworming pills provided an additional 30 days of schooling. In contrast, the same amount donated to fund scholarships only resulted in 0.3 additional days of schooling. Immediately afterward, we measured donors' attention to cost-effectiveness information by their ability to recall the information presented to them.

Results of the Online Experiment

The figure shows that the option to pledge motivated more participants to donate, increasing the total amount donated by 21.2%. These additional contributions were entirely directed towards the more cost-effective charity, raising its share of the total donations from 62.4% in the control group to 70.7% in the pledge group. Survey data shows that donations in the pledge group were more likely to come from participants who were aware of the significant difference in cost-effectiveness between the two charitable options. Therefore, we attribute the impact of the pledge option on participants' charity choices to the increased attention paid to cost-effectiveness information.

Our results demonstrate that it might pay off for highly effective charities to let donors pledge, even if they could try collecting the money immediately. As giving pledges exist in various forms, such as charitable bequests in wills or public declarations to donate a specific percentage of one's wealth or income, these findings have implications for practitioners. For example, some fundraising platforms, like The Giving Pledge, already rely entirely on pledges without asking donors to decide on the charities that will benefit at the moment of the pledge and demonstrate impressive success in raising money from the world's wealthiest individuals. Additionally, our study highlights how giving pledges could assist donors in planning the amount and timing of their gifts over an extended period — a feature that practitioners and previous studies may have overlooked.

MORSE recently supported my participation in the Science of Philanthropy Initiative (SPI) Conference, which connected me with new industry partners and opened doors for future research. We are now preparing field implementations of our original study in collaboration with Giving What We Can, The Giving Pledge (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), Doneer Effektiv, and Giving Multiplier to investigate whether our results replicate in real-world settings with individuals who are unaware of their participation in an experiment.

Also read

-

From Economics to Branding and Innovation: The journey of Patrick van Thiel

Patrick van Thiel’s academic journey began in Rotterdam before he found his true calling at Maastricht University in 1989. Drawn by the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) system, he quickly excelled academically, earning 90 credits in just one year. However, it wasn’t until he discovered his passion for...

-

Rethinking Higher Education in an AGI World: Reflections from the MINDS Workshop

With artificial intelligence (AI) developing at a rapid pace, conversations around its future impact are becoming increasingly urgent. While artificial general intelligence (AGI) — systems that could rival or exceed human-level performance across tasks — remains a highly debated concept, it cannot...

-

Discrimination makes women want to work less

Recent research by scientists at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and Aarhus University in Denmark shines a new light on the gender pay gap. Discrimination makes women want to work fewer hours.