Traditions with an aftertaste

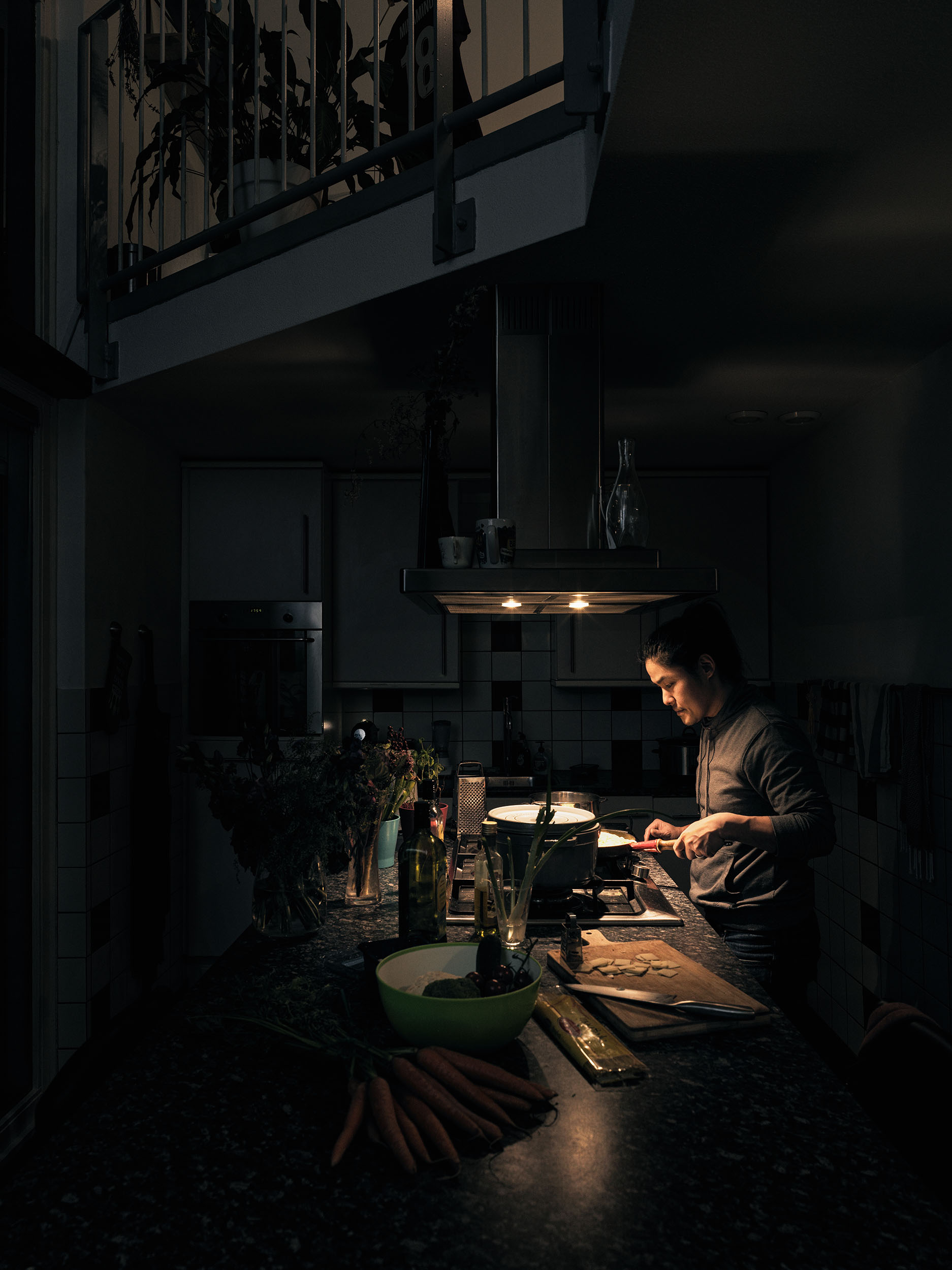

Mark Kawakami, assistant professor of Private Law, grew up in Japan and Hawaii. Omotenashi, Japanese hospitality, was drilled into him from an early age, but when it comes to food, he prefers the spicy cuisines of Thailand or Mexico to that of Japan. “Japanese cuisine is about savouring the purity of the ingredients, whereas I like strong flavours.” Here he speaks about traditions, his love of finger food, his son Sam’s favourite food—and pizza Hawaii. “That’s not a thing, period.”

Mark Kawakami spent his early years in Japan with his mother and grandparents. He has little to no memory of his father, who left after his parents divorced when he was a toddler. “We lived in Kobe, a large port city. My grandmother was a well-respected teacher of ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arrangement, and she was even congratulated by the Japanese royal family for her contribution and dedication to ikebana. At home she taught up to 300 students in one day, so there were always people coming and going. My mother worked as a Japanese-English interpreter and translator, and my grandfather was already retired. My first fond memories of food are with my grandfather. Every afternoon around five, he’d drink sake or beer, which meant accompanying snacks— or as we call it, otsumami. Nice fatty appetisers, but also things like cheese and cold cuts. He’d share them with me while I sat on his lap watching baseball or sumo wrestling.” The tastiest snack they ever shared was a fish they caught together. “He cleaned the fish that same day, fried it and dripped some ponzu, a citrus sauce, on it. So good, my mouth waters at the thought of it. I still love finger food, like fried chicken or nachos.”

Mark Kawakami is assistant professor of Private Law. He has a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from New York University and has studied at Johns Hopkins University, Columbia University, the United States Military Academy at West Point and the University of Minnesota Law School. He obtained his master’s in International Business at Tilburg University and his PhD at Maastricht University.

East meets west

When Kawakami was 10, his mother decided to move to Hawaii. For her work, ostensibly—but also for his education. “My kindergarten teacher told my mother I wasn’t really suited for the Japanese school system, which is very authoritarian and hierarchical. I struggled with that,” he laughs. “I wasn’t happy about leaving my grandparents, but I’m glad I was able to go to schools in the States.” There he was introduced to very different flavours: his taste for Thai, Korean and Mexican cuisine developed in New York. He also became aware of his Japanese tendency to try to please others by cooking elaborate meals without actually asking what they like. “That’s part of omotenashi. In Japan, you’re supposed to put huge amounts of effort into figuring out what others might like without bothering to ask them; it’s a sign of hospitality, and it takes time. Even as a boy I’d help to serve tea and coffee with a little treat on the side for all the people traipsing in and out. I remember when I was about 11 years old, I went to a Michael Jackson concert in Hawaii with my mom, which was great, but we had to leave halfway through because she had to prepare dinner for her guests.”

Tradition with a twist

Living in the Netherlands, Kawakami is happy that he can let some of those Japanese values go: it makes life a lot easier. “Traditions are valuable, but they can hinder creativity and innovation. In Japan, food is deeply rooted in tradition. My mom is now back there, living with my grandmother, and I normally visit every New Year. The traditional New Year’s food is osechi, a box containing 50 different small bites, which looks absolutely perfect. Every bite means something: a certain fish represents beauty, or a particular fast-growing vegetable represents growth in your career. My mom and my grandmother used to spend weeks making exactly the same box every year. As a boy I found this beautiful and magical, but now I also see it as somewhat confining, and a form of culinary stagnation. My favourite cookbook is by the Italian celebrity chef Massimo Bottura. In Italy people value their grandmother’s traditional recipes too, but he shows how you can reinvent them, while still respecting the essence of the recipe.”

The way to the heart is through the stomach

But his sense of omotenashi is more persistent than he thought—and not always appreciated, he says. “My wife calls me ‘the feeder’. She doesn’t like it when I bring her food without her asking. It makes her feel obliged to eat something she may not even feel like eating.” His son Sam (one and a half years old) is unequivocal on this front, too. “I once made a really nice meal for him, with a bit of chicken, rice and broccoli, but he simply refused to eat it. Instead, his current favourites are bananas and grapes,” he beams. Kawakami is over the moon with his family, but when it comes to cooking and eating, a lot has changed. “I still love to cook with lots of chillies, herbs and strong flavours, and I still cook often, because I find it relaxing. But now it’s mainly about it being healthy: lots of vegetables, little salt and sugar, and definitely not spicy at all. Actually, I’ve kind of returned to Japanese flavours, even though I’m still not a big fan of it”, he smiles. “But now I ask first what they would like to eat, rather than cooking what I think they will like… most of the time.”

Also read

-

In the upcoming months, the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences will share tips on Instagram on how to live a healthier life. Not just a random collection, but tips based on actual research happening at our faculty. The brains behind this idea are Lieve Vonken and Gido Metz, PhD candidates...

-

Frederik Claasen, the head of policy at our partner organisation Solidaridad Network on the opportunities and obstacles facing smallholder farmers in their data ecosystems.

-

Do you often write news items or texts for a website? Do you regularly conduct interviews or translate scientific information into “plain language” and would you like to improve your skills? Then register for the summer course ‘Journalism and Effective Writing’, which is taught by Riki Janssen...

- in Human interest

- in Researchers

- in Students