“I want to make girls like me stronger”

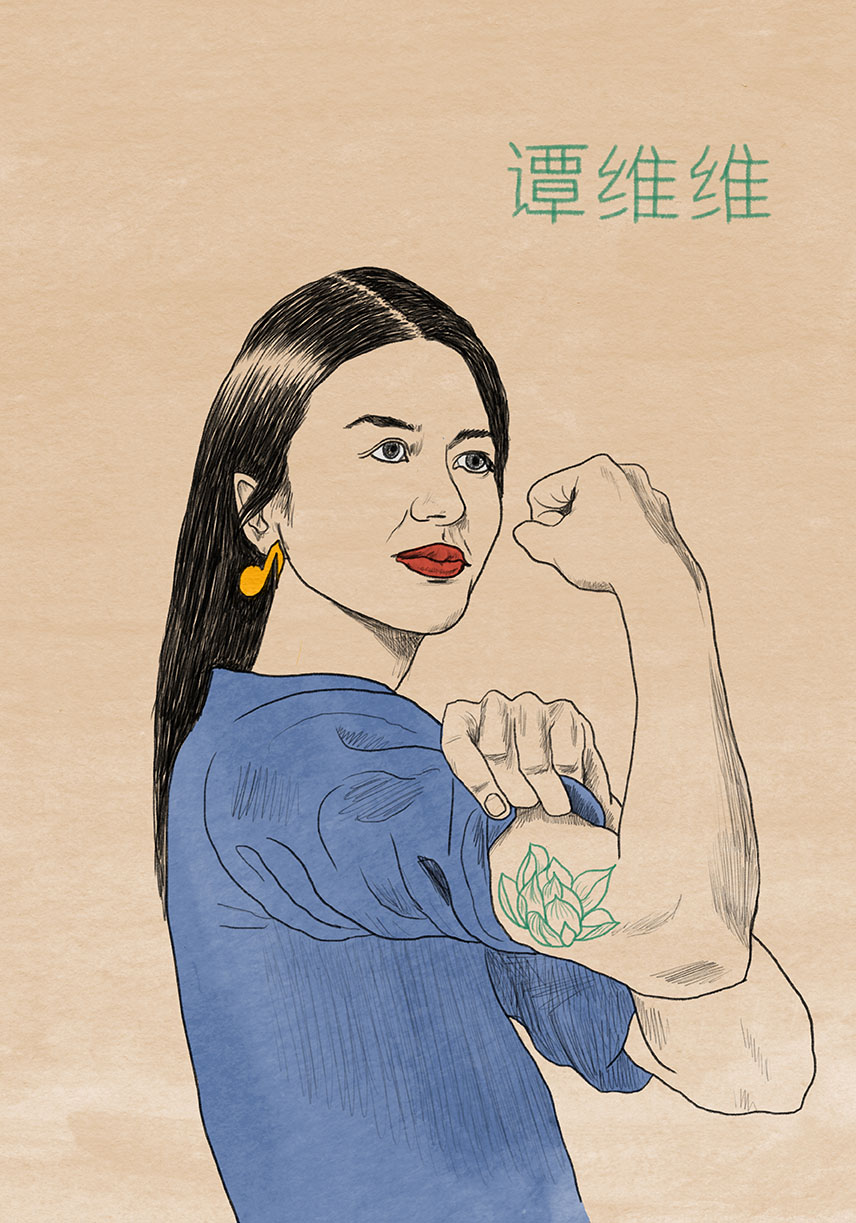

It’s a rare feat, but not impossible. The first paper ever written by Jiaru Zheng, a second-year bachelor’s student in Digital Society, was published as a journal article. The paper focused on the pop music album 3811, in which singer Tan Weiwei advocates for the status of women in China. “It’s the first pop album I know of that addresses topical women’s issues such as domestic violence and gender inequality in China. That’s very brave, and I admire her for it.”

Tan Weiwei is not widely known in China, particularly among Zheng’s generation. The 40-year-old singer is seen as neither young nor commercial enough. “She’s classically trained, sings at a high level. It’s not easy to sing along to. My generation prefers rappers and hip-hop. Kris Wu is a good example—he’s very popular.”

For Zheng, Tan Weiwei is interesting not only musically, but sociologically too. “She dares to point out the negative sides of how the Chinese view women. Usually the emphasis is on a positive ideal: that Chinese girls should always be happy, sweet, gentle and charming. That’s a traditional male image of women. It implies that for a girl, getting an education is not important. But getting married and having children is—you should take care of your husband and children.”

These values continue to prevail, especially in rural and inland areas. Zheng herself grew up in Guangzhou, a large, prosperous city near Hong Kong, and her parents, who both studied English, are relatively open minded. “My mother works and can otherwise do what she wants, but only because my father approves. Which is clearly not right. The man is the boss and the woman is seen as a second-class citizen—that’s a big problem. The Chinese government wants to convey a purely positive image; abuses such as violence against women are ignored. You won’t find anything about it on Chinese Twitter.”

Jiaru Zheng: “I bought this doll in the Netherlands. I’m holding it because she represents girls like me, girls I want to take care of and make stronger.”

De Beauvoir in China

Zheng was aware from an early age of the unequal position of men and women in China. One book that influenced her deeply is The second sex by Simone de Beauvoir. “She says women don’t take care of each other, they take care of the opposite sex: their father, their husband, their son. After reading her book, I wanted to be the kind of woman who took care of other women. I want to fight alongside other them for equal rights for men and women, even if that’s not easy in China. Fortunately, more and more women of my generation see the same need.”

Despite having been banned in China, MeToo is currently the strongest feminist movement there, Zheng says. But there are other promising initiatives by and for women. “The government mandates nine years of education: six years of primary and three years of secondary education. After that you can, but don’t have to, spend another three years at high school. For many girls from poor families, that’s not an option. If a choice has to be made, boys are given precedence. But a woman named Guimei Zhang has started a free high school for girls all over China with her own money. That’s very important: equal opportunities for men and women start with education. Many girls who went to that school are now doctors or teachers.”

More and more women of her generation are choosing to study instead of getting married. “My ultimate goal is to get a PhD. That’s what I want above all else.” Her first academic publication means a lot to her. “It’s hugely inspiring, and who knows, maybe I’ll also be able to publish my bachelor’s thesis.”

Freedom is happiness

Sociology, communication, culture, women’s studies; these are the topics that interest her. Because science, economics and technology are seen as more valuable, Chinese university programmes in her fields of interest are still in the initial stage of development, Zheng says. So she was pleased when she came across the Bachelor of Digital Society in Maastricht. “It’s a very good, professional programme that explores sociological themes in depth. And here in the Netherlands you’re free. I want to wear the clothes I want to wear, I want to be a hot girl; in China that will get you labelled as a whore. Last year I went to the Pride Parade in Amsterdam—something like that is unimaginable in China.” She plans to stay in the Netherlands for the time being, and hopes her studies will contribute to a fairer world for women.

Jiaru Zheng co-authored the article ‘Stigmatization of women in Chinese society: A case study of Tan Weiwei’s album 3811’ with Yimiao Huang from Sun Yat-sen University. The article was recently published in the proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Public Art and Human Development (ICPAHD 2021) (pp. 391-396). It is also listed in the Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI).

Also read

-

In the upcoming months, the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences will share tips on Instagram on how to live a healthier life. Not just a random collection, but tips based on actual research happening at our faculty. The brains behind this idea are Lieve Vonken and Gido Metz, PhD candidates...

-

With the project 'About not being an Einstein', made possible by a grant from the Diversity & Inclusivity Office, Anke Smeenk wants to ensure that being gifted is more widely recognised at Maastricht University.

-

This story starts in 2016, when Aaron Martin is still studying International Business in Maastricht. He is surprised by the growing anti-European sentiment at the time. Together with some fellow students, he wants to raise a positive voice. And what better way to do so than with a European football...