A unique case of looted art

It started with an international phone call from the lawyers of the Norton Simon Museum in California. Not long after that, assistant professor Lars van Vliet served as an expert witness in a important court case. The stakes: a diptych by Lucas Cranach the Elder, which the heiress of the Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker claimed had been looted. After a court case lasting 12 years, she came away empty-handed – partly due to the research of Lars van Vliet.

Van Vliet specialises in comparative property law. “I’ve always been interested in art, but I could never have imagined being involved in a case like this”, he says. Here he reflects on an “instructive and exciting period” in which he scoured dozens of metres of archived records. A race against the clock to reconstruct postwar Dutch legislation and jurisprudence – largely uncharted territory – and explain it in all its intricacies to lawyers at the prestigious US law firm Munger, Tolles & Olson.

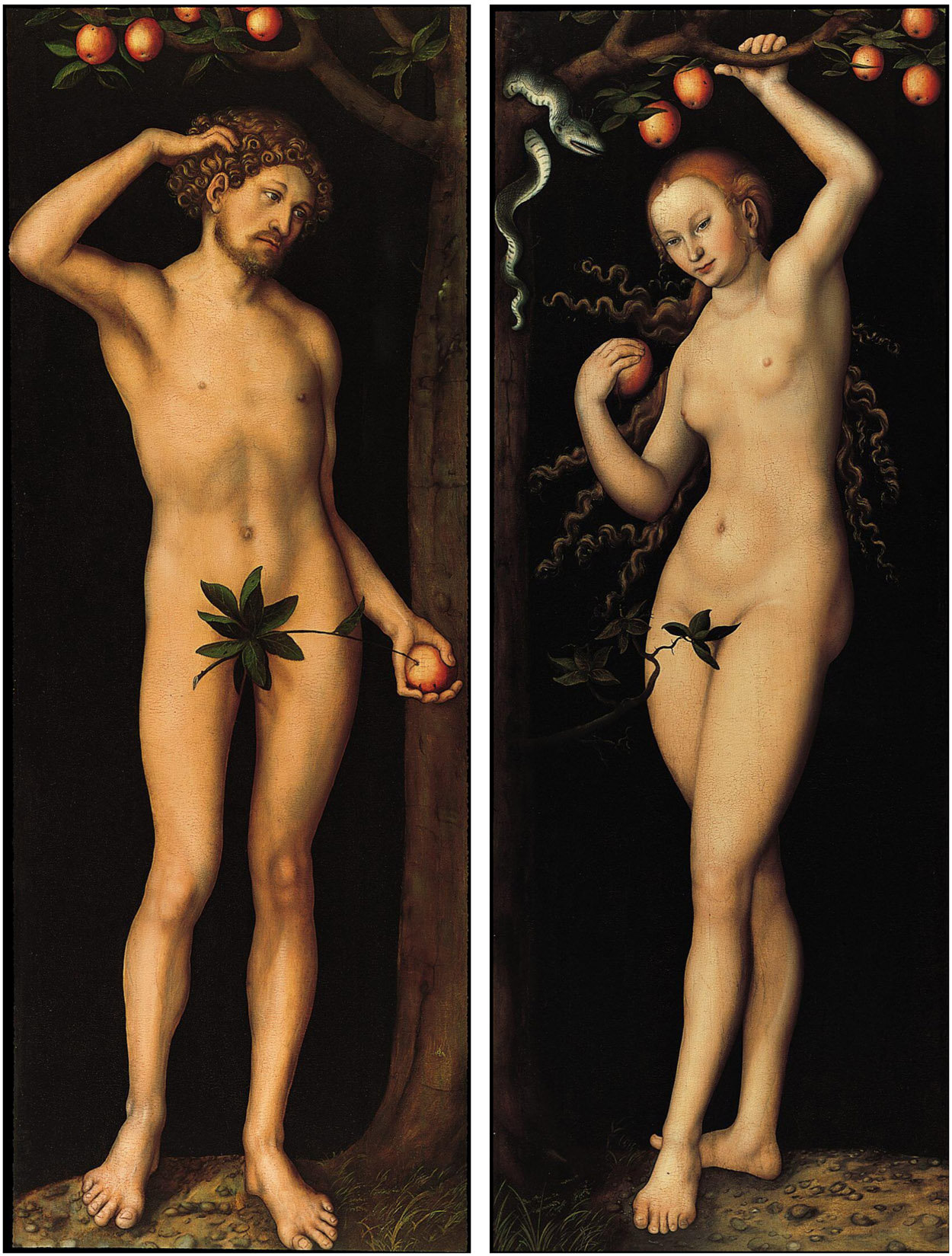

In this, he succeeded. Van Vliet’s story was watertight, withstanding a seven-hour deposition. More importantly, based on his input the lawyers managed to convince the District Court that the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena is the rightful owner of Cranach’s diptych Adam and Eve. “It was a fantastic experience to work together with such wildly intelligent lawyers. No matter how complex the material, they always immediately understood what I meant.”

Lars van Vliet studied law at Maastricht University, where he obtained his PhD in 2000 and currently works as an assistant professor in Comparative Property Law and Art Law. He has taught at universities in Scotland, Aruba and South Africa.

Van Vliet emphasises:

“This is not a typical case

of theft of Jewish art:

a considerable sum was paid for it, and after the war the victim consciously decided to keep the money”

Goudstikker and Göring

The tale of the Goudstikker art theft begins in Amsterdam in 1940. Jacques Goudstikker is a major art dealer in Western Europe. Shortly after the German invasion, he flees by boat to England with his wife Dési and their son Edo. He dies on board, the result of a fatal accident. Back in Amsterdam, his remaining staff are paid a visit by representatives of the Nazi chief Hermann Göring, an avid art collector.

“You’d expect Göring to just take whatever he wanted, but that’s not how it went”, Van Vliet explains. “At the start of the war he apparently had enormous amounts of money. After lengthy negotiations, he acquired more than 1100 works of art at purchase price.” For Goudstikker’s real estate – his country house in Oostermeer, Nijenrode Castle and the office building on the Herengracht – he receives a token fee: a business friend of Göring’s gets hold of the portfolio for half its market value.

After the war

Even before the war ends, the Dutch government in London legislates to reverse these types of forced transaction. Victims can have the purchase agreement annulled, which means the goods sold under duress have to be returned – but so too do any payments received for them.

“We found documents from Goudstikker NV showing that the company deliberately chose to reclaim only the real estate, not the art collection. After all, it had received a considerable sum for the art. The company would not only have to pay this money back, leading to liquidity problems, but would also have to establish a new art gallery and find staff for it. In short, it was a legitimate and conscious business decision.”

When Goudstikker NV decides not to reclaim the paintings, they become, pursuant to postwar legislation, the property of the Dutch State. And from that moment on, the State is free to do with them whatever it wants. This is how the diptych Adam and Eve comes to be sold in 1966 to an heir of the Stroganoffs – aristocrats from Russia – who in turn sells it to Norton Simon.

Heiress Marei von Saher

The widow of Goudstikker’s son Edo, Marei von Saher, has spent years fighting for the return of as many paintings as possible. The most important weapon in her arsenal is a recommendation by the Dutch Restitution Committee, which in 2005 saw more than 200 works returned to the heiress from the Dutch State.

“That spurred her on to claim back the rest of the collection”, says Van Vliet. “Only the Norton Simon Museum dared to go to court, probably because of the unique history of Cranach’s diptych. It was already stolen art when Jacques Goudstikker bought it from the Soviets at an auction in Berlin in 1931. The communists stole art from the nobility and the church to invest in agriculture. When Goudstikker bought the diptych from the Stroganoff collection, he knew he was buying stolen art. So it’s a unique case of looting by both the communist Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.”

Front line

The Soviet theft aside, the District Court ruled only on whether the Dutch State became the lawful owner of Goudstikker’s paintings in the 1940s and 1950s. Based on Van Vliet’s research, the judge decided that this was the case, meaning that Adam and Eve will stay in the Norton Simon Museum. “This is not a typical case of theft of Jewish art: a considerable sum was paid for it, and after the war the victim consciously decided to keep the money”, Van Vliet emphasises. The diptych probably never lawfully belonged to Goudstikker in any case, having initially been stolen by the Soviets. “In contrast, there are many other cases in which enforcing a strict statute of limitations is morally unacceptable, and in which you have to look for other solutions to return looted art to the original owners or their heirs.”

For Van Vliet, this was his first hand-on experience with a case of looted art. “It was intense, but at the same time it gives you energy, as well as knowledge to share with your students. Our plan here at the faculty is to offer several courses in the field of art law, and ultimately develop them into a master’s programme. So for me it’s important to keep cooperating on lawsuits. To further expand this specialism, you really have to have work on the front line.”

Also read

-

The Globalisation & Law Network organised a roundtable on Circular Economy and Trade, promoting a discussion about circular economy regulations in the European Union and Brazil.

-

How can and should the government respond to the current low participation in the national immunization programme? Can certain forms of coercion be justified? The book Inducing Immunity? Justifying Immunisation Policies in Times of Vaccine Hesitancy provides answers.

-

On 20 March 2024, the Globalisation & Law Network hosted the seminar featuring Professor Jacob Öberg (University of Southern Denmark).

- from Faculty of Law