Screening or deterring investments into the European Union?

This article discusses the European Investment Screening Mechanism (ISM) – a legal instrument to control international mergers and acquisitions involving non-European investors. ISM aims to safeguard economic and societal resilience by protecting Europe’s key assets to ensure national security and public order. Yet, its implementation lacks transparency, which hampers evaluation and provides scope for misconduct and deterrence that could work against its proclaimed aims. The analysis of this policy is part of an ongoing research agenda.

Background

Originating from the ambition to foster the EU’s strategic autonomy in a national defense and security context, rising geopolitical tensions, the Covid-19 pandemic and other events resulted in a much broader Open Strategic Autonomy agenda involving regulations in a range of European business, digital and trade domains (Clingendael Report, 2021). With the overall aim to enhance the resilience of European economies, enterprises and societies, one element of this agenda is the protection of critical infrastructure and technology.

As a step towards this goal, the EU adopted a regulatory framework to promote the implementation of Investment Screening Mechanisms (ISMs) to control and monitor international mergers and acquisitions by non-EU entities (European Commission, 2019). “Europe must always defend its strategic interests and that is precisely what this new framework will help us to do”, says the former president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, in this context. “We need scrutiny over purchases by foreign companies that target Europe’s strategic assets”. Responding to concerns about rising economic protectionism, Austria’s former Minister for Digital and Economic Affairs adds that: “[t]his is not about closing down our markets but about acting responsibly. We are determined to keep our technology sectors and key infrastructure safe.”[1]

By adopting a formal screening mechanism, EU member state governments become legally entitled to screen, condition, prohibit or even unwind non-EU foreign direct investments (FDI), if they are considered a potential threat for national security and public order. Yet, while the European framework lays out certain features of such a screening mechanism, mentioning broad sectors and non-EU buyer characteristics, actual implementation and decision power rests with the member states, which leads to a patchwork of regulatory guidelines and practices that are difficult to understand.

This blog is written by Karsten Mau, Assistant Professor of Economics at Maastricht University, School of Business and Economics (SBE). Next to this he is Program Director of the BSc EBE/IB Emerging Markets Specialization at SBE.

His research focuses on topics in international trade and development, globalization and structural change.

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions: an early policy evaluation

As part on an ongoing research agenda on economic interdependence and international supply chains, I investigate the effects of implementing Investment Screening Mechanisms (ISMs) on general patterns in cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) involving non-EU buyers (Mau, 2023). Although EU and member-states’ government officials claim that most international transactions have been approved even without need for formal screening (European Commission, 2023), the legal uncertainty that arises from the possibility of being screened (and prohibited) might have a deterring effect on overall M&A activity, reducing FDI into the EU.

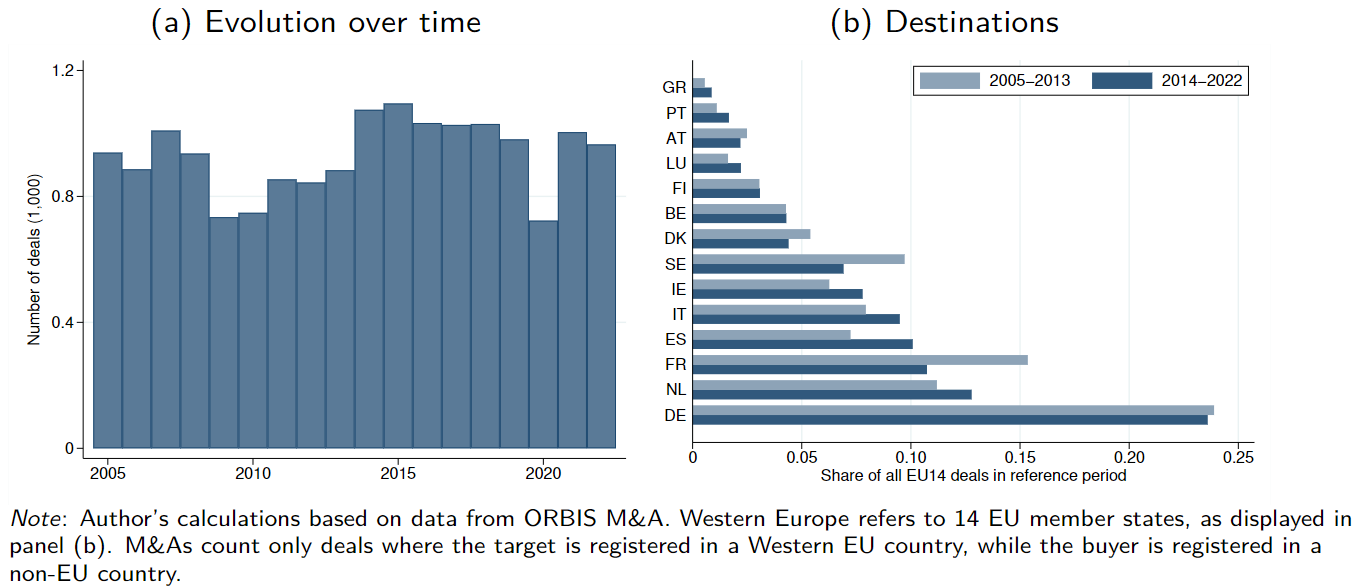

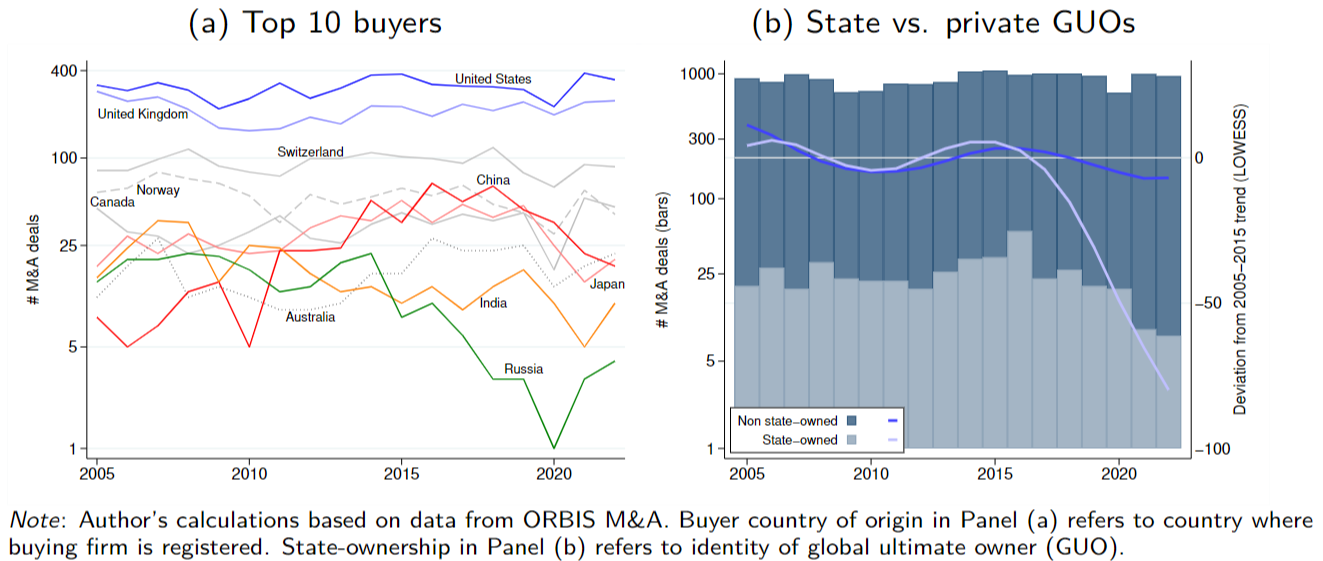

Figure 1 displays aggregate numbers of M&A activity involving non-EU buyers and EU targets. Significant but temporary reductions are observable during the Global Financial Crisis, the European debt Crisis and the COVID19 pandemic. However, since the formal adoption of ISMs (starting with forerunners in the years 2012-17, but spreading more widely only in 2020 and after), the overall trend has been slightly decreasing. Figure 2 displays the 10 most frequent countries of origin of buyers, as well as a tendency that the share of state-owned or controlled buyers has decreased in the past years.

Figure 1. Number of M&As by non-EU buyers in Western Europe, 2005-2022

Figure 2. Identity of non-EU buyers in Western Europe, 2005-2022

More formal statistical analyses suggest that, indeed, EU countries adopting an ISM in line with the European regulatory framework saw significantly larger decreases in overall M&A activity – a result that is confirmed by Vera Eichenauer and Feicheng Wang, who study investment screening in a broader sample of OECD countries. Interestingly, despite the evidently declining activity of Chinese and state-controlled investments into the EU (see Figure 2), both our studies cannot confirm that the possibly deterring effects of screening on cross-border M&As we identify are driven by China or state-controlled investors. An explanation could be that the country’s own industrial policy agenda (e.g. Made in China 2025) has been adjusted to foreign investments that contribute to knowledge and technology transfer to promote their own economic development progress. A gradual decline in Chinese foreign investment activity can also be observed in other regions.

Discussion and further research

The empirical findings allow only for a first and preliminary evaluation of the effectiveness of the promoted screening mechanisms, whose proclaimed aim is to ensure national security and public order in the EU by protecting key sectors form foreign interference, while remaining generally open to investment. The evidence suggests that some deterring effects materialize in strategically sensitive sectors. However, they can be detected also in more aggregated data, which could be an indication that the adopted screening mechanisms deter investments also in non-sensitive sectors. More detailed analyses can shed light on the prevalence and relevance of such negative externalities, for example, by observing which sectors exactly are deemed critical by individual member states.

The annual reports of the European Commission present only indicative numbers on the sectoral concentration of screening procedures, where manufacturing sectors and information and communication technology (ICT) industries are most frequently involved. Within manufacturing, about more one third of the screenings undertaken in 2022 related to planned acquisitions of firms that operate in semiconductor, communication, data processing, or cybersecurity industries. Other prevalent subsectors related to energy, health, transport, aerospace, and defense. Despite such broad alignment of screening activities with the promoted sectorial focus of this policy tool, uncertainty remains on which transactions will actually be subjected to higher scrutiny and potential rejection. The most recent figures suggest that the proportion of notified deals subjected to screening has increased, of which about 10 percent were either authorized conditional on mitigating measures or fully prohibited. Another 4 percent of deals was withdrawn by the parties before a formal decision was made. Higher transparency will be beneficial for both potential investors – seeking to invest into European firms – as well as for policy makers who seek to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of their tools and instruments.

A related question arising from the adoption of formal investment screening mechanisms pertains to their actual implementation. The identification of strategically critical sectors and industries is not trivial, given complex business-group structures and an intricate web of input-output relationships in modern economies. To take advantage of such uncertainty, industry lobbyists might try to influence the design of screening mechanisms in ways that work against their actual purpose. Moreover, the discretionary nature of ultimate decisions provides scope for bad policy making and suboptimal decisions. While most EU member-state governments keep their records of investigations and decision outcomes confidential, insights into these procedures would significantly contribute to an enhanced accountability of these procedures.

Further collaborative activities in the context of my research agenda will focus on shedding some light on these questions. Parts of these efforts focus on developing methods to infer input-output relationships for manufacturing sector activities at highly disaggregated levels. These can be used in subsequent steps to infer critical inputs and potential bottlenecks of selected production activities, which will be further useful for determining critical sectors and industries in EU member states and elsewhere. Moreover, collecting and evaluating the few existing documentations of investment screening procedures and their eventual outcomes and decisions, will shed light on the prevalence of potentially discriminatory behavior in the approval of prohibition of mergers and acquisitions by non-European investors. Altogether, this research agenda contributes to a more transparent documentation and evaluation of policies that proclaim to cater the interests of European citizens by providing for a more secure and resilient economy and society.

[1] The quotes stem from a related news article at EUbusiness.com, from 22 November 2018.

Also read

-

Maastricht Sustainability Institute (MSI) of Maastricht University School of Business and Economics (SBE) has successfully applied for funding in the ‘Driving Urban Transitions’ program of NWO/ JPI Urban Europe. Three new transdisciplinary projects with international partners have recently started...

-

SBE took first place in the Rotterdam School of Management Star Case Competition (RSMCC). The competition welcomed 16 top-level international business teams of four students, who were tasked with tackling two real-life business cases.

-

Higher air pollution increases the likelihood of people voting for opposition parties rather than ruling parties. This is the major finding of research by Nico Pestel, a scientist at the Research Centre for Education & Labour Market (ROA) at the Maastricht School of Business and Economics.