Detect bacteria while you wait

It all started with an unexpected discovery. Bart van Grinsven, associate professor of Sensor Engineering, figured out how to detect microparticles—bacteria, toxins and proteins—in a liquid using a rapid testing method based on heat transfer. Through the startup Sensip-dx, Jaap Drenth is now turning ‘Bart’s technology’ into a commercially viable product. The testing device will be made available this year to the food industry.

The discovery was more of a slow burn than a classic Eureka! moment. “It was more like, that’s odd, what’s going on here?” Bart van Grinsven explains. “I sort of stumbled across it. It was only after ten months of removing measurement errors but getting the same result that I finally realised this is completely new.” In essence, he had found that by measuring heat transfer, he could detect when small particles attached themselves to a surface. At first this worked with DNA, then with cells and later with even larger entities, such as bacteria.

The technology’s strength lies not in the highest possible degree of detection. “Perfection is often the enemy of the good,” he says. In other words, we should not shy away from a solid improvement in the quest for something optimal. “We never achieve the precision of a PCR test, but we don’t have to. You could compare it with the rapid test for covid. Our technology delivers good results quickly, cheaply and reliably, and for many applications is unbeatable. All you need is two thermometers and a power resistor, which is unprecedented.”

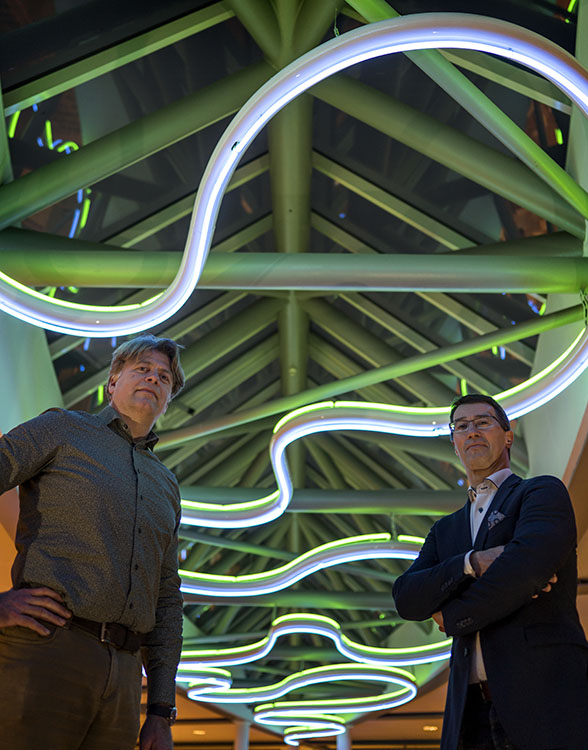

Bart van Grinsven and Jaap Drenth

Golden opportunity

When Jaap Drenth appeared on the scene, plans for the establishment of the startup Sensip-dx were already underway. “Through the valorisation department of the Brightlands Health Campus, which commercialises new technologies, I came across this patent-protected invention with vast possibilities,” he explains. “In principle, it can be used wherever contamination can occur: in blood, urine, water, food. It’s a big improvement on existing techniques and really makes a difference. To succeed in this space, you have to offer an affordable solution to a problem that’s keeping someone awake at night.”

This turned out to be the case in the food industry, which has long struggled with the time-consuming nature of existing techniques for detecting live bacteria. “Usually you have to culture samples and wait up to three days for the results,” Drenth says. “Our technology lets you do this in 15 minutes, so you can assess whether harmful bacteria are creeping in during the production process.”

In addition, a golden opportunity presented itself. Drenth learnt that existing testing methods cannot distinguish between live and dead bacteria. “This complicates things with products like pasteurised milk, which always contain fragments of dead bacteria and thus yield positive test results. Our technique can actually tell the difference—a unique selling point that has the entire food industry excited.”

Jaap Drenth is CEO and co-founder of the startup Sensip-dx, which is developing and commercialising the technology. He holds a master’s in Business Economics and Information Sciences from Tilburg University and completed the Register Controller professional master’s at Maastricht University.

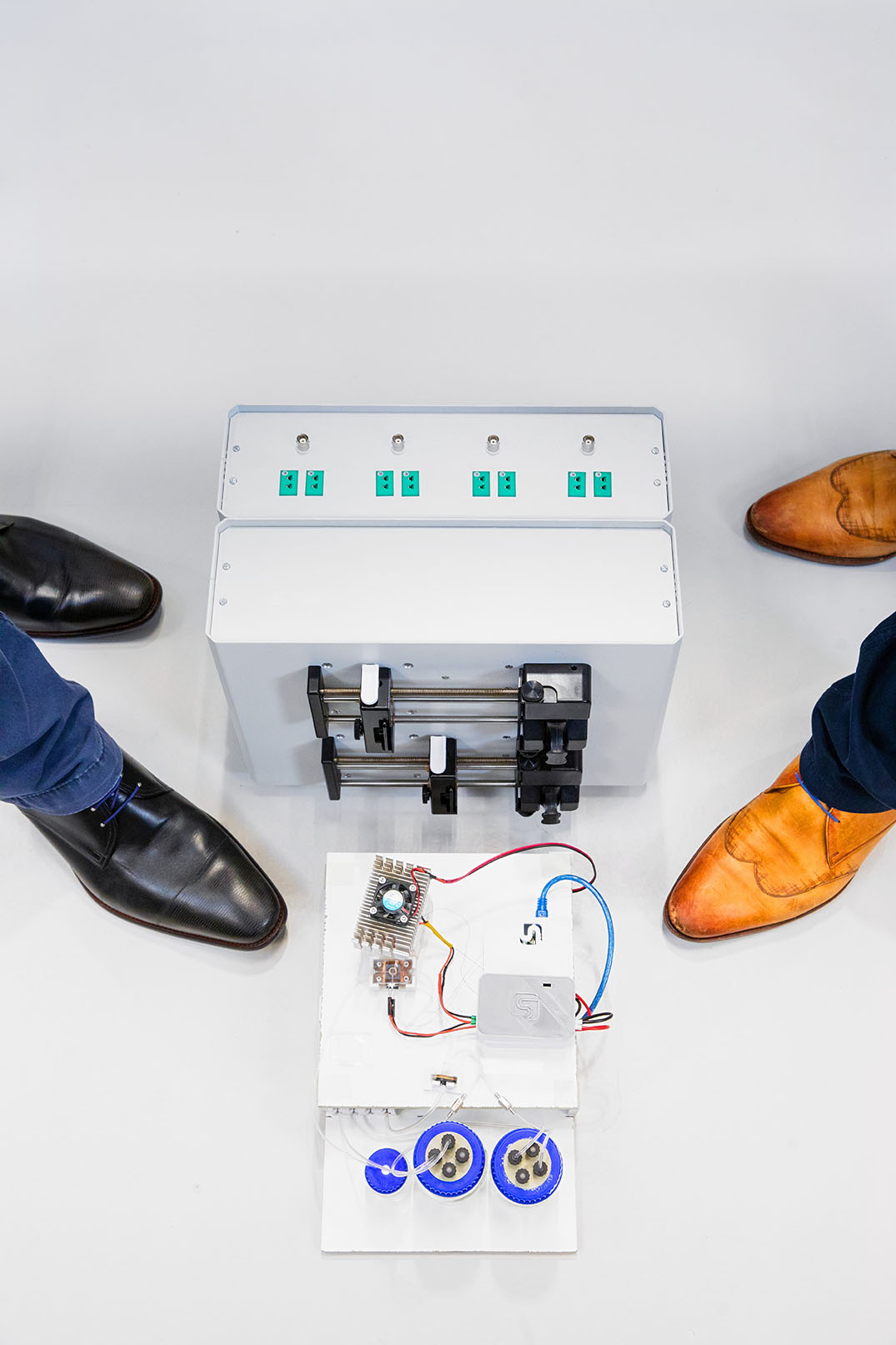

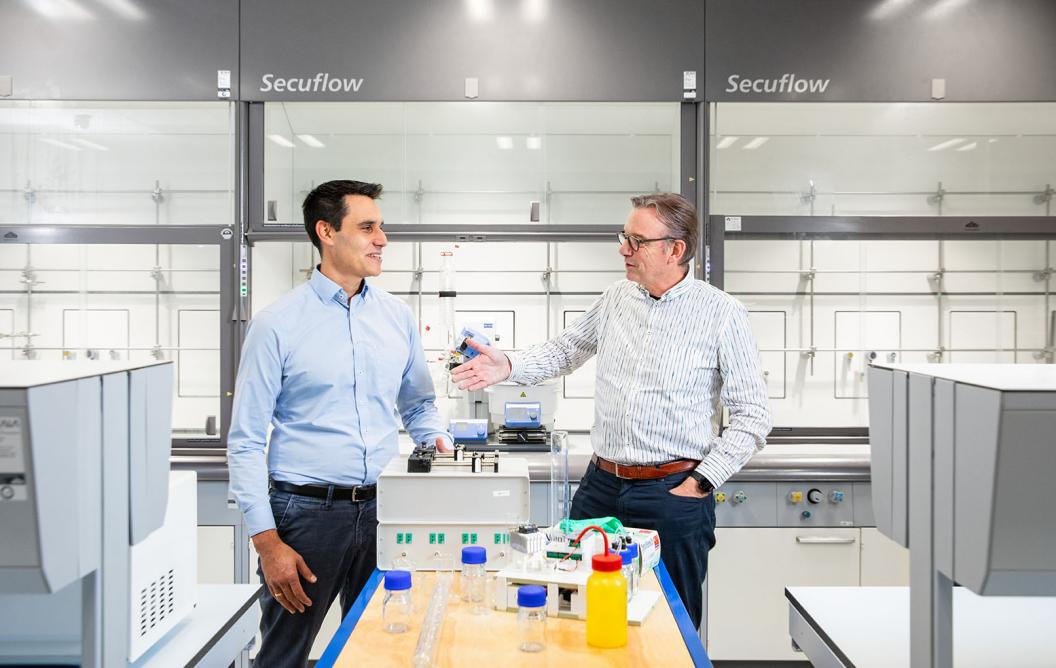

Frankenstein prototype

The next step is to convert the technology into a practical device. The large machines employed in the laboratory are not suitable for commercial use. “They make investors run for the hills. And you have to be able to produce large numbers of the device in a short time,” Van Grinsven says. They now have a working model, but according to Drenth, “It’s still a kind of Frankenstein prototype, large and clumsy. We’re working on developing a more convenient device that you can just toss a few millilitres into, press a button and get a result after 15 minutes.” This year, they will move into batch production and, ultimately, the commercial launch of the device.

A drawn-out certification process is certainly on the cards, but Drenth sees no reason to twiddle his thumbs in the meantime. “You can spend that time looking for killer applications—problems that clients are currently experiencing, which Sensip-dx can solve with no regulatory burden.” Take the testing of fermentation products and probiotics. Probiotics are live, good bacteria that are sometimes added to food, but the amount of bacteria in a product is difficult to determine. “Applications like that make customers happy. Plus you generate income and can develop more generative applications while complying with the rules for certification.”

Bart van Grinsven is associate professor in Sensor Engineering at the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Maastricht University. He holds a master’s in Bioelectronics and Nanotechnology from Hasselt University and a PhD in Biosensor Research. He specialises in the development of electrochemical and heat-transfer-based sensors.

Springboard

If the rapid testing method is successful, the food industry will form a good springboard for other business cases. The testing method lends itself to use on vitamins, toxins, viruses and proteins. It could detect Legionella in water pipes or toxic substances in polluted water, Drenth says. The technology could also be used for medical purposes, such as detecting proteins in urine. “But that’s a conservative world; you’re dealing with big, influential players, and that equates to money. To create something new in that world you first have to succeed in another sector.”

Both see benefits of the technology for society at large—not least in poorer countries and remote regions. “The test may be able to detect parasites quickly and easily in blood, drinking water or faeces,” Van Grinsven says. “That could be valuable in the case of malaria, where it’s crucial to determine at an early stage whether a parasite is involved. In the future, I’d like to conduct fundamental research on this application.” The invention could one day even transcend planet Earth—a company affiliated with NASA has already inquired about the technological possibilities for future space missions to Mars.

Hans van Vinkeveen (text), Philip Driessen (photography)

"It’s still a kind of Frankenstein prototype, large and clumsy. We’re working on developing a more convenient device that you can just toss a few millilitres into, press a button and get a result after 15 minutes."

Jaap Drenth

Also read

-

Computers are already capable of making independent decisions in familiar situations. But can they also apply knowledge to new facts? Mark Winands, the new professor of Machine Reasoning at the Department of Advanced Computing Sciences, develops computer programs that behave as rational agents.

-

If we were to replace plastic with paper or glass, would the environment benefit? Surprisingly, no, says professor of Circular Plastics Kim Ragaert. She is calling for an alternative approach aimed at increasing awareness of and knowledge about recycling.

-

Gerard van Rooij, professor of Plasma Chemistry, was the first PhD candidate of Ron Heeren, university professor and director of the M4I institute. Together they reflect on a pioneering period in which they took the first tentative steps in the development of imaging mass spectrometry.