Abuses in the adoption system

We're republishing this article from November 2019 following the decision of the Dutch minister for Legal Protection Sander Dekker to immediately (8 February 2021) suspend the adoption of children from abroad. This decision was taken after the publication of a damning report on the system of so-called intercountry adoption in the Netherlands.

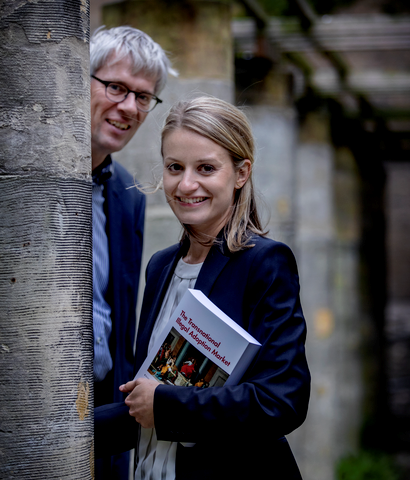

Elvira Loibl defended her PhD in early 2019 for her research on illegal practices in the world of international adoption. “As a criminologist, I know that every transaction has a dark side. I wanted to bring that to light.” André Klip, professor of Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure and the Transnational Aspects of Criminal Law, was one of her three supervisors – although she made their work easy. “A lightning-fast PhD that ends in a cum laude: that’s rare”, Klip says.

Like most people, Loibl had a positive image of adoption from distant lands. We tend to think of healthy, happy babies, rescued from a heart-breaking situation and ending up in the loving arms of adoptive parents. But the reality is often different, her research shows. “The problem is that there is high demand, especially for healthy babies, as in that romantic picture we all have. It’s a market for children and the demand exceeds the supply.”

Harrowing

Her PhD was part of the interdisciplinary research programme ‘Good governance in international child transfer’ at the Maastricht Centre for Citizenship, Migration and Development (MACIMIDE). Loibl, originally from Austria, focused on international adoption to the Netherlands and Germany. Her supervisor André Klip had a personal interest in the project: many years ago, he adopted two children. “Sometimes the results of Elvira’s research were quite confronting. You know you can’t rule out the possibility of abuse entirely, but I was shocked at how little the adoption system can do to resolve or prevent it.”

Criminal

The practices for obtaining children for adoption are often downright criminal. “Children who aren’t in need of adoption are abducted or purchased”, Loibl explains. “They’re taken from orphanages, where they were placed only temporarily by the biological parents. Or mothers are lied to: after giving birth they’re shown a dead baby, while their healthy child disappears abroad. The illegally acquired children are then ‘laundered’: their birth certificates and other documents required for adoption are forged. And the authorities in the countries concerned do too little to stop these abuses; there’s just too much poverty and corruption.”

“Our children are from South Africa, which in principle has strict rules”, Klip says. “The mother has to give permission immediately after the birth and then reconfirm her decision after 60 days. But this rule is easy to circumvent. The mother disappears and doesn’t show up again, or another woman signs the statement. As for documents: when we and our newly adopted son went to a paediatrician for a medical check-up, the information we’d received turn out to match the reality. But as our doctor said, that’s rare. To give an example: the document might say a child is four, when he’s actually six.”

Elvira Loibl is an assistant professor at the Department of Criminal Law and Criminology. She obtained her master’s degree in law at the University of Vienna and her master’s in Forensics, Criminology and Law at Maastricht University. In May 2019 she obtained her PhD cum laude for her dissertation ‘The transnational illegal adoption market: A criminological study of the German and Dutch intercountry adoption system’.

André Klip is professor of Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure and the Transnational Aspects of Criminal Law. He previously worked at Yale Law School in New Haven and the Max Planck Institute in Freiburg. He specialises in European criminal law and international crimes.

Outside the system

Many children are also brought to the Netherlands or Germany outside the formal adoption channels. “There are various tactics for this”, Loibl says. “A couple goes to Russia, and at the border coming home they say the woman gave birth in Russia unexpectedly. A man claims to have had an affair in the Philippines. The mistress doesn’t want the baby, but the wife has forgiven him, so he’s taking responsibility for the child and bringing it home. Or a couple brings a child into the Netherlands on a tourist visa and doesn’t return it to the country of origin. Embassies are becoming increasingly alert to these types of practice.”

The child’s best interests

Such children are rarely sent back to their own countries, Klip explains. “The ultimate goal of adoption has been achieved. The child has a loving family who takes good care of him. And because the best interests of the child are always paramount, you’re almost never going to remove him from the environment to which he has grown accustomed.” What about the biological parents? “It’s very difficult for them to demand that their child be returned. They’re usually poor and vulnerable, with neither the money nor the opportunity to look for their child. It did happen once: a couple from India suspected their son had been brought to the Netherlands. They came over and demanded a DNA test, but they were turned down because the authorities decided it wasn’t in the child’s best interests. They had to go home empty-handed.”

Authorities

In 1995, 55 countries signed the Hague Adoption Convention, which sets out ethical and legal standards and requirements to prevent illegal practices. This did not bring an end to the abuses in the adoption world. “It’s hard for the home countries to meet these stringent standards”, Loibl says. “And the checks performed in the receiving countries are inadequate. The authorities always claim the abuses only happened before 1995, but this research shows that they’re continuing.” There is hope, Klip says. “In the Netherlands, a special committee has been installed to investigate illegal adoptions in the 1970s and 80s.”

Advice

What can the receiving countries do? Loibl: “Check the documents thoroughly: do they look forged or homemade? Alarm bells should also go off if a lot of money is being charged for a child.” Klip: “There’s a lot of room for improvement in the delicate process between birth and placement. Especially in Germany, where each state has its own adoption agency with its own procedures. The Netherlands has one central authority, which is becoming increasingly alert to ruses. They can’t ignore this type of research. The media are also becoming more open about it. Germany is lagging behind in this area.”

Text: Margot Krijnen, originally published 19 November 2019

Photography: Harry Heuts

Also read

-

What does it mean to live and work in a city with an international university? When do you notice the university, and how does it benefit you? We asked Maastricht native Stefan Vrancken (50), who works as an associate notary. In his spare time, Vrancken is also an amateur historian and genealogist...

-

Alisa moved from Moscow to the Netherlands at 17 years old to become a first-year Regenerative Medicine and Technology (RMT) bachelor’s student. Turns out Alisa’s adventurous spirit pushes her to brand-new things, such as the RMT bachelor’s programme and her hobby Tribal Fusion dancing.

-

SBE took first place in the Rotterdam School of Management Star Case Competition (RSMCC). The competition welcomed 16 top-level international business teams of four students, who were tasked with tackling two real-life business cases.