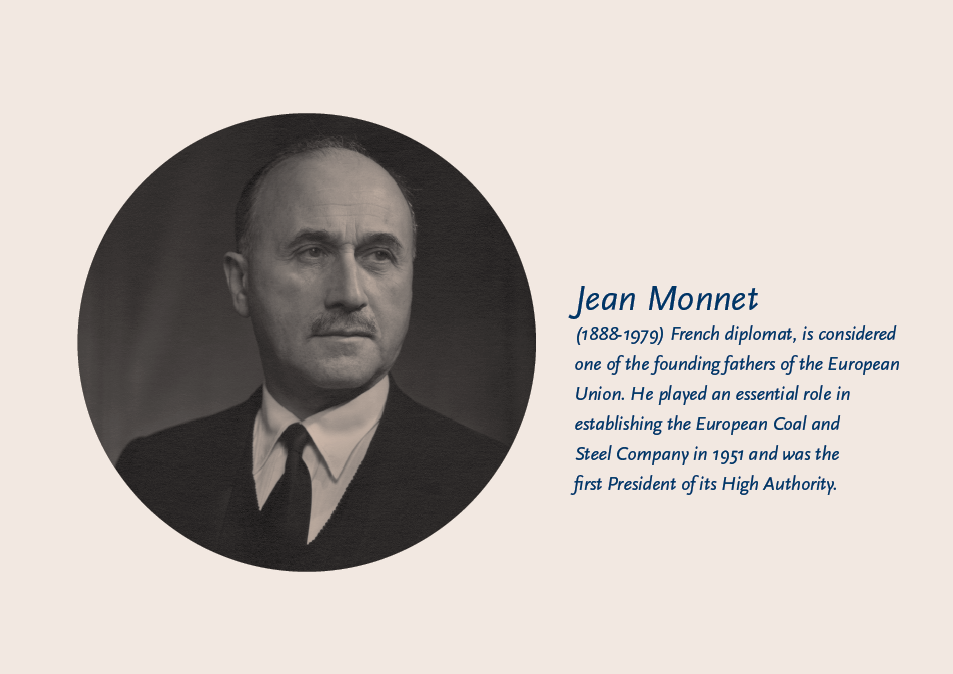

Jean Monnet

Jean Monnet (1888-1979) is, in some ways, an unlikely person to be honoured by having a university hall called after him. Indeed, Monnet left school at the age of sixteen, never obtained a university degree, and indeed never started university studies. He grew up in the city of Cognac as the son of a négociant, a trader in the famous local fortified wines. From the age of 19, the young Jean started to travel across the world to sell the ‘cognac Monnet’ (a brand that still exists today). He had no time to undertake university studies. So, if he was not a ‘great jurist’, why can a law faculty such as that of Maastricht justifiably honour him?

Jean Monnet is buried in the Pantheon in Paris among the great personalities of French history, though his main merit for France (and for the Netherlands and other European countries) was his role as a pioneer of the European integration process. He was a politician, but an unusual one, as he never once campaigned for elected office. Through his business contacts in the United States, and the management experience he had acquired, he came to play a central role, after the second world war, in organising France’s economic reconstruction with American aid. From this vantage point, he came to the conclusion that economic cooperation between states could offer a key to the construction of peace and prosperity in post-war Europe. As he later reflected, ‘coal and steel were at once the key to economic power and the raw materials for forging weapons of war. To pool them across frontiers would reduce their malign prestige and turn them instead into a guarantee of peace.'

He mused on this idea in March 1950 while on a walking holiday in the Alps and submitted it to the French foreign minister Robert Schuman. The latter was seduced by the plan and announced it to the press in a speech he gave at the Quai d'Orsay (the seat of the ministry of foreign affairs) on 9 May. That day is still celebrated every year, in Brussels, Maastricht and other places, as ‘Europe day’, since this event got the ball rolling that led, one year later, to the creation of the European Coal and Community Treaty, among six states, and a few years later to that of the European Economic Community, which both morphed much later into the European Union that we know today.

In order to make international cooperation effective and long-lasting, one needs credible institutions. Monnet stressed the importance of independent, supranational, institutions who could pursue the common interest without being directly affected by national preferences. Monnet himself was chosen to chair the first such supranational institution, the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community, the predecessor of the current Commission of the European Union. After resigning from that function, in January 1956, he established the Comité d’action pour les Etats-Unis de l’Europe, which became an influential advocacy group in the 1960s. He believed in the importance of gathering a European elite of political and economic actors who would help to advance the integration process and who would, in turn, persuade the citizens of Europe.

His strategy of fostering an institutional approach to solving international problems was embodied in the European Treaties. This approach is now celebrated as the ‘Monnet method’ which, according to many scholars, has been key to the successful development of European integration. The Monnet method is essentially a pragmatic one. One cannot expect the old (or new) nation-states of Europe to openly relinquish their sovereignty and transfer most of their powers to a United States of Europe in one go, as the euro-federalists had hoped. Instead, one needed to put in place European institutions that would exercise a small part of the states’ sovereign powers, and if that worked well, it would create in-built dynamic (often called a ‘spill-over process’) towards ever new domains, eventually leading to a European Union with a broad range of powers and strong independent institutions. Monnet was, in fact a European federalist, but he sought to advance his cause without making too many people frightened about it.

Nor was Jean Monnet scared of crisis situations. His own post-war experience had shown him that a crisis also creates new opportunities. In his own words (and turning to French for once), ‘les hommes n’acceptent le changement que dans la nécessité et ils ne voient la nécessité que dans la crise.’ This message, and his life time experience, are particularly useful as the European Union faces a number of major challenges today. Even though doomsayers like to predict the disintegration of Europe, Monnet’s message is that more, and better, European cooperation is often the best answer to the new challenges facing the countries of Europe.

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

Other blogs:

Also read

-

-

Throughout the EU, the rights of asylum seekers come under pressure. Overdue policy changes remain stuck in negotiations because of lacking political will. It is up to the European Commission to step up and protect the fundamental rights of asylum seekers.

-

With its judgment in case Stichting Rookpreventie Jeugd and Others (C-160/20) of 22 February 2022, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (Court of Justice) has set a fundamental milestone on the legal status and consequences of incorporating global standards in EU...