Larger than life

On 21 December the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) held its official closing ceremony. The Tribunal is thereby a thing of the past. But it lives on in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, first and foremost in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), but also in Serbia and Croatia. In their legal systems, the Tribunal left clear traces.

How the ICTY is still making law in the Balkans

On the one hand, it triggered prosecutions and trials for international crimes at national level. On the other hand, much of its jurisprudence and legal practice found its way into the national legal systems of the Western Balkan states, which are much better off now.

In the countries of the former Yugoslavia, the Tribunal was throughout its 24 years long existence either enthusiastically welcomed (mostly in Bosnia and Herzegovina) or fiercely hated (mostly in Croatia and Serbia), with the reactions running along ethnic lines. In Serbia, people feel that the Hague Tribunal has disproportionately prosecuted and convicted Serbs, and punished them more severely than members of the Croatian, Bosniak, or Kosovo-Albanian communities. In Croatia, people still believe that their “Homeland War” was a legal defence war against the Serbian aggressor – which legitimises war crimes as the necessary evil. Just as acquittals of members of the other ethnic groups, convictions of members of one’s own group have always caused heavy emotional reactions as most of the convicts are still seen as heroes despite their convictions for international crimes. Just recently, this could be observed again at a memorial ceremony held in Zagreb for Slobodan Praljak, who committed suicide while still in courtroom after being convicted on appeal for ethnically cleansing the Herzegovina of Bosnian Muslims in 1993. At this ceremony, a Catholic priest compared Praljak with Jesus and presented him as the saviour of his people. Vladimir Lazarević, a former general convicted for crimes of deportation and forcible transfer in Kosovo, was welcomed by government members and cheering masses at the airport of Niš, after having served his sentence. He was recently appointed teacher at the Serbian military academy.

Within the population, the Hague Tribunal has polarised. And even many members of the political elites had to do their utmost to hide their animus for the Tribunal, which they only did in order not to become internationally isolated. But since the ICTY has enjoyed great respect amongst the majority of jurists in the region, it became a role model for national courts that took over its jurisprudence and legal practice, leaving a clear legacy in the legal systems of the region, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Hope of the Victims

The Tribunal’s most important legacy is arguably that it triggered proceedings for international crimes in the countries of the former Yugoslavia. In BiH, it lobbied and advised the decision makers to set up specialised a prosecution service and a specialised war crimes chamber at the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since 2005, they deal with the most complex cases, while less complex and lower profile cases are handled in BiH’s regions. Also in Serbia and Croatia, political pressure from the EU, NATO and the US was high enough to set up specialised institutions there as well and to start prosecuting and trying international crimes.

At state level in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 185 persons have been convicted to 2449 years of imprisonment until now, though the majority of cases is adjudicated at regional level. The political and societal will to address the country’s war crimes past is high and the trials are omnipresent in the public debate. In Croatia and Serbia, the number of trials is much lower – in Serbia, for instance, only 78 persons have been convicted to 925 years of imprisonment until now. Especially in Croatia, political will to address the country’s past is almost non-existent since the country’s accession to the EU and the lack of political pressure mechanisms since then. The words of the Croatian Prime Minister who described the verdict against Slobodan Praljak and his five co-accused as a “deep moral injustice”, just as the president of the Croatian parliament qualified it as “unjust”, exemplify that Croatia has become unwilling to deal with its past. Also in Serbia, the success of war crimes trials heavily depends on political will – which is volatile at best. In 2003, the driving force behind establishing the war crimes chamber at the Belgrade High Court and founding a specialised war crimes prosecution unit was then-Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić. It was also him who surrendered Slobodan Milošević to The Hague. Shortly after that, in 2003, Đinđić was murdered. When the chief war crimes prosecutor Vladimir Vukčević stepped down in January 2016, the Serbian parliament delayed electing his successor for almost 1.5 years. Snežana Stanojković eventually stood up against her co-candidates, probably partly because she had announced to make prosecuting crimes where Serbs were the victims her priority – as opposed to crimes committed by Serbs. Nevertheless, and even if dealing with the past initiatives do not receive much political support in Serbia and war crimes trials play no role in the public discourse, there is hope. 2017 was the year that the until now most complex trial started, the first concerning crimes committed in Srebrenica in July 1995. Even though the eight men are “only” accused of war crimes and not of genocide (the prosecution claimed they couldn’t determine the accused’s genocidal intent), the fact that Srebrenica is at all finally addressed in Serbia is a positive sign.

These national trials complement the work of the ICTY and send the signal that the law is being enforced again also at national level and that impunity will not prevail. Through the trials, the suffering of victims is acknowledged and their findings can contribute to establishing the truth about what happened during the wars. This can rebuild trust into state institutions and the rule of law. This development is, not even 20 years after the last Yugoslav wars ended, a great achievement.

Broadening the Horizon and Professionalisation

Apart from that, the Hague Tribunal has left clear traces in the legal systems of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also of Serbia. Both countries – BiH in 2003 and Serbia in 2011 – have adopted new codes of criminal procedure, which are partly based on the ICTY’s legal procedure. Judges at the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina regularly use ICTY jurisprudence and practice in order to fill the gaps of their own code of criminal procedure or to clear up ambiguities therein. The same applies to the application of the new criminal code that codifies international crimes – war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. That way, national courts follow up on the at times progressive ICTY interpretation of certain offenses. For instance, in some landmark judgments the Tribunal acknowledged that sexual violence such as rape, genital mutilation, or sexual slavery is used as a weapon of war, or even worse: as a means of genocide. Continuing this line of jurisprudence is beneficial especially for the victims. Also the European Convention for Human Rights is more and more often used as a legal source in order to ensure a fair trial for the accused. A defence counsel once commented upon this by saying: “Applying ICTY jurisprudence on a daily basis taught our judges to get acquainted with international sources of law and to apply them. And most trivially: they had to learn to read in English.” Using ICTY law and practice has thus broadened the horizons of legal practitioners. The use of a variety of sources can legitimise the outcome of the criminal process and increase legal consistency and certainty.

In addition, following the example of the ICTY, criminal courts in the countries of the former Yugoslavia increasingly professionalised. For instance by introducing so called status conferences, a concept copied from The Hague. Status conferences, where all parties to the proceedings – bench, prosecution, defence – meet, help to structure, focus, and thereby speed up the trial that sometimes lasts for several years. Everyone benefits from that: the accused who has a right an expeditious trial, the victim who doesn’t have to wait for ages for the verdict, and the state for whom long trials cost a lot of money. Another example where the ICTY has shown national courts the way is the use of technologies in the courtroom. For instance, victims can now testify via video link so that they don’t have to appear in person before the court, if they are unable to travel. But the Tribunal also triggered broader, more important innovations: all countries have well-functioning witness protection programs now, which are essential for the success of a criminal trial, but more importantly, for life and limb of witnesses.

It becomes obvious that this legacy of the Yugoslav Tribunal goes beyond the field of war crimes adjudication. Witness protection programmes, applying international and European law in criminal proceedings, or a modern court room also enhance the quality of other criminal proceedings. The new way of conducting trials can thereby contribute to a better judicial system, which strengthens trust in the rule of law and boosts a culture of law.

The Unexpected Legacy

The ICTY was established in 1993 by the UN Security Council as an alternative to military intervention in the Yugoslav wars. At the time though, no one believed that it would ever take up its work, let alone deal with 161 suspects. The Tribunal proved them wrong. With its success it didn’t only contribute to bringing justice to victims of the wars. It also considerably advanced the development of international humanitarian and international criminal law. In 2002, the permanent International Criminal Court was established, which wouldn’t have happened without the Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and its sister Tribunal for Rwanda. The example of the ICTY also shows that international criminal courts not only send the signal that impunity will not be granted. They also have an important function serving as a role model for national courts which will have to deal with thousands of international crimes cases. Guiding them in this work can have a lasting positive effect on national legal systems.

This is a slightly modified and translated re-post of an opinion piece by Kei Hannah Brodersen published in the German IPG journal

| More blogs on Law Blogs Maastricht |

Other blogs:

Also read

-

The well-known British James Bulger case is ‘celebrating’ its 25th anniversary. This revives the debate on how we should deal with children suspected and convicted of serious crimes.

-

Instead of protecting the victims of Burundi, the current government shields those who are responsible. The problem with such impunity is that it de facto “legalizes” violence as no accountability is created.

-

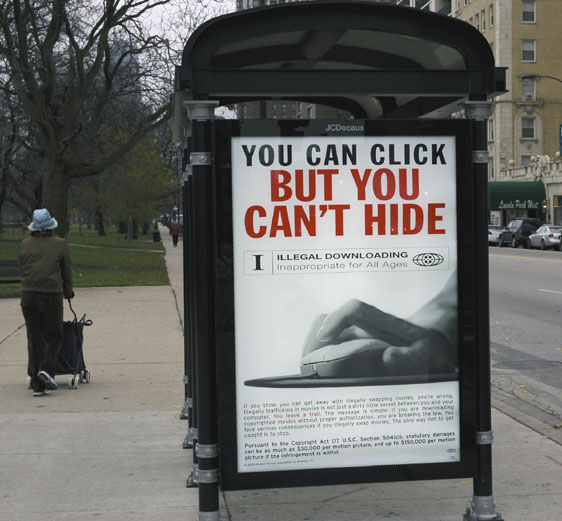

Where in 2010, about 40 per cent of the population downloaded music, the figure is now a quarter, partly because of the arrival of Spotify. The best strategy to avoid illegal downloading, according to Bastiaan Leeuw, is a mixture of punishment and temptation.