Transformations: A complex and crucial topic for research and politics

In the ever-evolving landscape of research and politics, the concept of purposive transformations has been growing in importance over the past years. However, the literature on transformations is diverse, lacking coherence, and necessitating better theorisation and cross-fertilisation. Typically, the term "transformations" is used in opposition to a past situation or future scenarios that differ significantly from the present.

This blog post delves into various meanings of the term across different fields, including sociotechnical system transitions, socio-ecological transformation, transformative social innovation, urban transformations, governance of transformations, and political economy. For those interested in delving deeper, a reading group on transformation mechanisms and patterns will start after the summer.

The problem of disparate definitions

Let us first explore critical perspectives on state-led transformations, and contrast them with the more optimistic views found in sustainability studies. These critical perspectives are mostly found amongst political scientists and political economy scholars, who are often sceptical about the state's ability to achieve positive transformations. They argue that past efforts have primarily benefited the powerful rather than the vulnerable. Notable examples include the Highlands clearance, where tenants were forcibly evicted in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, and the enclosure movement, which privatised commonly used land in England and elsewhere. In his book Seeing Like a State, James Scott provides examples of failed state-initiated social engineering.

He attributes these failures to four factors:

- the administrative ordering of nature and society,

- a high-modernist ideology,

- an authoritarian state willing to use its coercive power, and

- a passive civil society unable to resist these plans.

Another perspective is offered by Karl Polanyi, an Austro-Hungarian political economist, anthropologist, and sociologist, who wrote about the transformation of society into a market society. For Polanyi, this transformation in modern Europe was not inevitable but historically contingent on the doctrine of laissez-faire and the gold standard. He also noted that this transformation sparked a countermovement demanding state-based protection.

In contrast, sustainability transitions studies typically present a positive view on transformative change. This perspective promotes alternative systems of mobility, energy use, agriculture, and land use through innovation policy and the phase-out of environmentally unsustainable practices. The field involves historical and contemporary analysis of niche and regime dynamics by transition researchers and studies of attempts to co-create transformative change by socio-ecological and transdisciplinary transition scholars.

While most transitions scholars would regard transformative change as something desirable, different definitions of system transformation appear in the literature, including:

- Social transformations: involving emergent political realignments and technological innovations that challenge incumbent structures (see e.g. Stirling’s work on the politics of energy choices).

- Transformations towards sustainability: fundamental changes in the structural, functional, relational, and cognitive aspects of socio-technical-ecological systems (see e.g. work by Patterson and colleagues on the politics of transformation)

- Transformative change: non-linear systemic shifts leading to qualitative changes in societies' cultures, structures, and practices (see e.g. Loorbach and colleagues’ review of sustainability transitions research).

In my own work, for instance in a 2007 study of shifts in waste management and sanitation systems I wrote with Frank Geels, we distinguish between a transformation and a transition. In our understanding, a transformation is an adjustment and re-orientation of a socio-technical system where existing regime actors remain dominant actors. This is in contrast to a transition, where new actors become dominant actors.

Transformative change and why it is difficult to achieve

Reflecting the core belief of sustainability transition research, the 2019 report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) states that the “goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors.” Here, transformative changes are defined as a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across these factors, including paradigms, goals, and values.

Similarly, the 2018 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report Global Warming of 1.5 °C emphasises that limiting warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels requires “transformative systemic change integrated with sustainable development”. This entails the upscaling and acceleration of far-reaching, multilevel, and cross-sectoral climate mitigation, alongside complementary adaptation actions, especially for pathways that temporarily overshoot 1.5 °C.

A few years before these discourses started to emerge in policy and governance spheres, I set out with colleagues across European universities to develop a theory on “Transformative Social Innovation”. In the outputs of this project, we defined transformative change as a change that challenges, alters, and/or replaces dominant institutions in a specific sociomaterial context. The focus here is on social relations, which are not just a means to an end but are positively desired.

In our understanding, achieving transformative change is challenging because systems involve interdependencies that cannot be altered by mere acts of will. Producers depend on suppliers and buyers, managers must satisfy shareholders, and politicians must balance demands for stability and change. While attractive alternatives are necessary, they require significant effort and time to become viable.

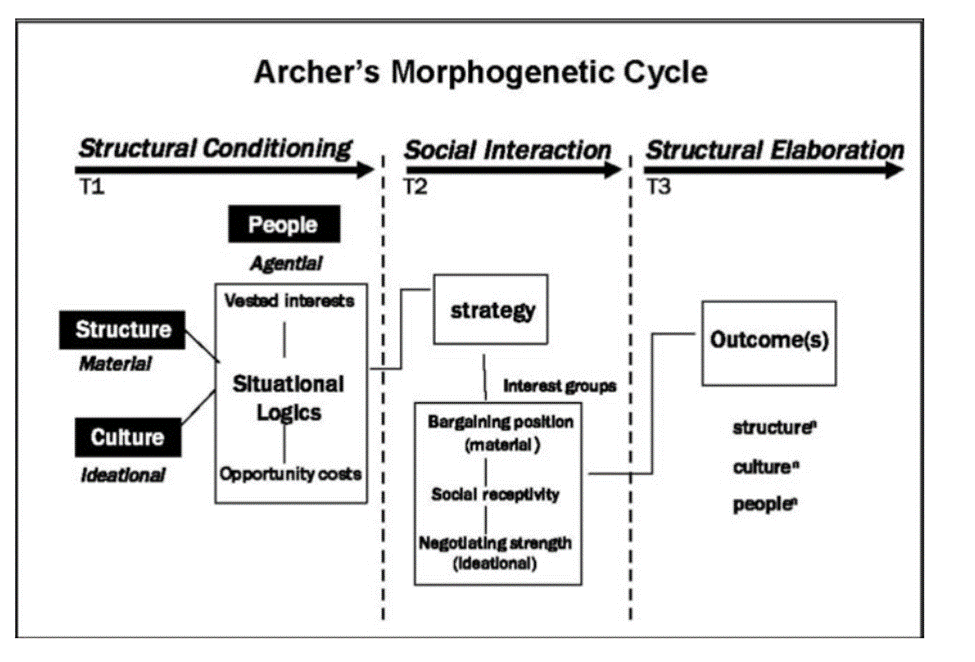

Another approach to transformation I want to highlight here is the morphogenetic cycle proposed by Margaret Archer, as visualised by Wong (2005, p.13). Archer combines structure, culture, and agency, viewing agents as formed by social structures—the formative experiences in schools, families, communities, clubs, and organisations they are or have been a part of—and by the widely shared societal expectations and aspirations of their time. The genesis of the agent occurs within the context of social structures involving social interaction. Over a larger time scale, these structures themselves change as a result of the activities and choices of historically situated individuals. This recursive relationship between actions and institutions can be broken, with changed mentalities both resulting from and driving transformations.

Similar to Giddens, Archer considers people as reflective beings, capable of viewing themselves in relation to others and alternative worlds (reflexivity). They can imagine futures and engage in collective action to achieve Real Utopia. The dynamics of institutional logics and transformations are complex and contingent upon circumstances and institutional work; it is never instantaneous or total but always situated and a matter of perspective. Institutional scholars Mahoney and Thelen identify four types of gradual institutional change, highlighting the coexistence of old and new rules and the dynamics stemming from tensions between them. The role of power and knowledge in social change is discussed by Flor Avelino and by Bob Jessop in a book chapter on governance and meta-governance.

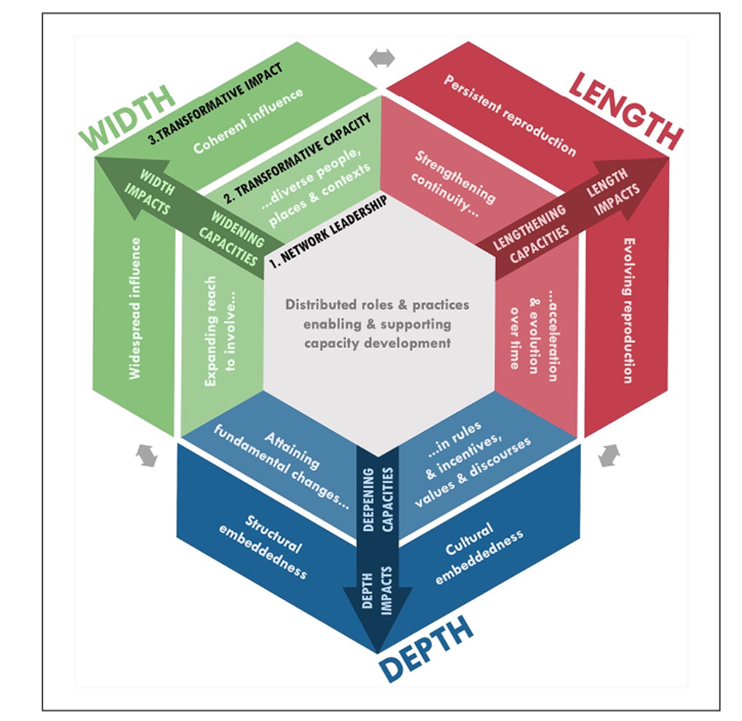

I also want to highlight the work by Tim Strasser, a PhD student at MSI. In an article co-authored with Joop de Kraker and myself, he distinguishes three dimensions of transformative change: Depth, Width, and Length. Depth refers to the novelty of values and associated practices and social forms. Width pertains to the geographic scope at which transformative change occurs. Length addresses the persistence and further elaboration of transformative practices, organizational forms, and institutional arrangements (Strasser, de Kraker, and Kemp, 2022). This model can be applied to various transformation processes, such as marketization, emancipation, the transformation of work (gig economy, peer production, democratisation, surveillance, and worker rights), and new forms of governance (more participatory, anticipatory, and network-based).

The politics and paradox of transformations

Transition and transformations have become increasingly the domain of politics and policy. The EU Green Deal and Dutch energy transition are examples of policy makers embarking on transformative change. Such transitions are purposeful, in contrast to emerging transitions that occur ‘spontaneously’. It remains to be seen how useful the distinction between emerging and purposeful transitions is. Any process of change, especially transformative change, involves steering by actors in society, including acts of resistance. A new source of opposition to the energy and agricultural transitions comes from populist parties who are anti-government, anti-elite, and anti-Europe. This demonstrates that transformations are unruly, conflict-ridden, infused with diverse meanings by actors, and influenced by different agendas and power dynamics.

At the other end of the spectrum, critics of capitalism call for a global shift towards a human and fair economic system, prioritising healthy ecosystems, healthcare, public services, education, and culture. They call for a “just” transition process which must incorporate elements and values such as inclusive social and regional dialogue, measures to mitigate negative effects on workers and regions and support for workers in declining industries to find new work. They also highlight the need for decent work and the protection of vulnerable households from energy poverty.

These cases of opposition and resistance show that transformations are a battlefield of politics, power plays, and cultural disagreements among experts and socio-economic groups. Vulnerable people are likely to be affected negatively unless special actions are taken. The risks of negative social or environmental effects are real, as shown by Benjamin Savocool in the study of land degradation and property dispossession in developing countries and many other scholars.

These discussions are also very relevant in an EU context as it has embarked on a coordinated approach to transform Europe’s economy through the Green Deal. Mission-oriented innovation policies as advocated by Mariana Mazzucato and a just transition fund are key elements. Actual policies and consequences depend on decisions by private and public decision-makers, as well as evolving ideas for steering and the knowledge used (called Knowings of governance by Jan-Peter Voß and Richard Freeman). Governance scholars distinguish between governance models for transformations, the governance of transformations, and transformations in governance (Patterson and others in an article in EIST). These models influence transformation policies and highlight how embedded actors can offer advice for disrupting well-established systems. In transformation processes, actors whose imaginations and practices are bound by existing structures become different actors due to changing circumstances (structural elaboration). This is the paradox of transformations.

Governing transformations: different views

This brings me to my last point. The science of managing transformations is evolving. For economists, carbon taxes are the principal instrument for achieving decarbonisation. Transition researchers draw attention to the barriers to such policies, the need for innovation policy and regulation, and dealing with the political economy of change. I strongly agree with the recommendations offered by Daniel Rosenbloom, James Meadowcroft and Benjamin Cashmore for an effective and just energy transition policy: embed the low-carbon transition in a broader transformative agenda, build societal legitimacy for climate policy, encourage the growth of constituencies with a material interest in climate-friendly transformations, and create a supportive ecosystem of institutions.

Social-ecological scholars actively look for leverage points for a transformation, using (participatory) systems analysis ((Karen O'Brien and Linda Sygnain in Perspectives on transitions to sustainability). They also pay attention to the need for resilience. Others consider the attempts at greening the economy as futile, given the growth imperative, and call for degrowth and exnovation, the purposive termination of existing (infra)structures, technologies, products and practices. Personal transformations are the aim of Presencing, “being open beyond one’s preconceptions and historical ways of making sense” so that one is “consciously participating in a larger field for change” to realize “the possibilities actually available to us”. It combines system thinking with obtaining an open mind, becoming less judgemental and less conditioned, and becoming a different person by connecting yourself to a greater purpose.

I have always been fascinated by the extent to which people are part of historical processes and the complex interaction effects between economy and society. With Harro van Lente I have written about this. To us, actors are myopically caught in processes of co-evolution, whose dynamics involve structural conditions and elaboration. A mind-first model, or a model of incentive-based change, fails to appreciate the role of practices, conventional ways of thinking and micro-politics of change. In a project with water companies (TransB), transdisciplinary research is used to promote integrative thinking and problem solving. This shows that research can also be used to bring on transformative change, through design thinking and dual track governance.

Relevant research and new reading group at Maastricht University

Transformations and their implications for policy, politics, and society are critically studied at Maastricht University. Transformation-oriented research includes work on urban transformations by Christian Scholl, Joop de Kraker, and Anique Hommels; the Transformation Flower Approach for leveraging change towards multiple value creation and institutional change by Patrick Huntjens (and myself); studies of electric mobility by Marc Dijk; and Job Zomerplaag's research on the everyday experiences and collective memory of transitions in energy infrastructure systems in the former mining area of Parkstad Limburg.

This body of work highlights the relevance of transformation studies while also revealing the fragmented nature of the scholarship, both in the academic community and within our own university. To address this fragmentation, I will initiate a reading group in September to discuss important articles on transformation. The focal questions will be:

- What societal phenomena are the topic of investigation and explanation?

- What causal mechanisms are identified for transformative change?

- What crucial insights do the literatures offer each other?

- How can transformative change be studied?

The reading group will meet once a month, at UNU-MERIT and possibly other venues. Everything is contingent, but it could be a transformative experience, and even if not, you will learn something new. You are welcome to join the group and become transformation literate.

(with thanks to Job Zomerplaag for editing the text).

This blog is authored by René Kemp, Professorial fellow at UNU-MERIT, Professor of Innovation and Sustainable Development at the Maastricht Sustainability Institute and co-lead of MORSE.

Also read

-

Billions of dollars in foreign aid could be spent more effectively if international poverty statistics weren’t so inaccurate. Says Dr Michail Moatsos, Assistant Professor at Maastricht University School of Business and Economics.

-

Anecdotal evidence imply that what ones sees in a sausage factory cannot be unseen, and such an experience somehow takes away something from the joy that stems out of the carefree consumption of such delicacies. In this blog entry about the international poverty line’s maladies, I don’t want to ask...

-

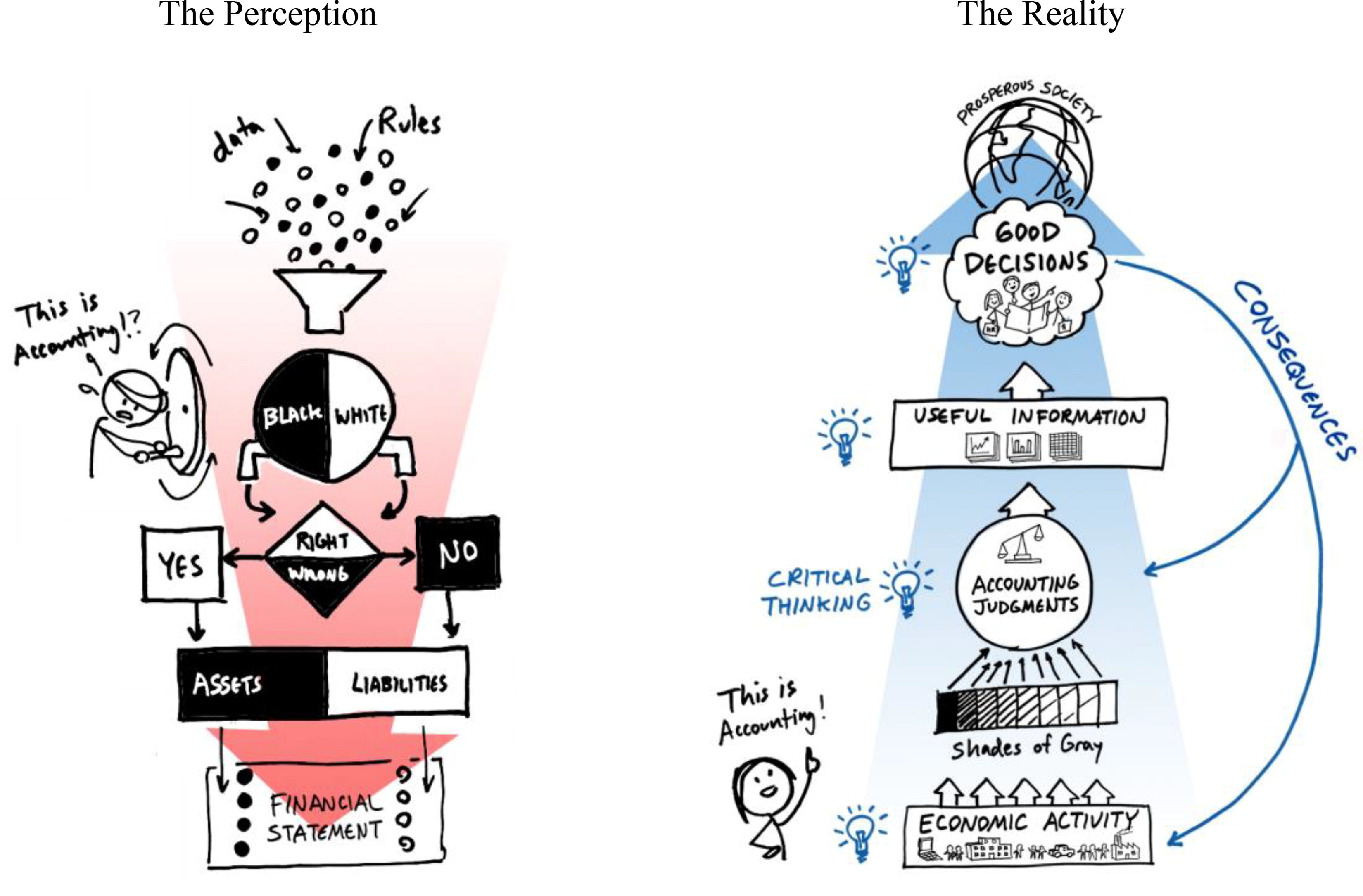

“Accountants will save the world”, said Peter Bakker about ten years ago in an interview with Harvard Business Review. Peter Bakker is a Dutch businessman, who serves since 2012 as the president of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development - WBCSD. The WBCSD is a global alliance of CEOs...