Can Accountants Save the World?

“Accountants will save the world”, said Peter Bakker about ten years ago in an interview with Harvard Business Review. Peter Bakker is a Dutch businessman, who serves since 2012 as the president of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development - WBCSD. The WBCSD is a global alliance of CEOs from more than 200 companies, who are committed to sustainable development.

Now ten years later, another interview with Peter Bakker has been published in the Chartered Accountants magazine where they exchange views with him about this statement.

What is accounting?

Before we get into the question of the role of accounting for a sustainable future, let's take a moment to consider what exactly accounting is.

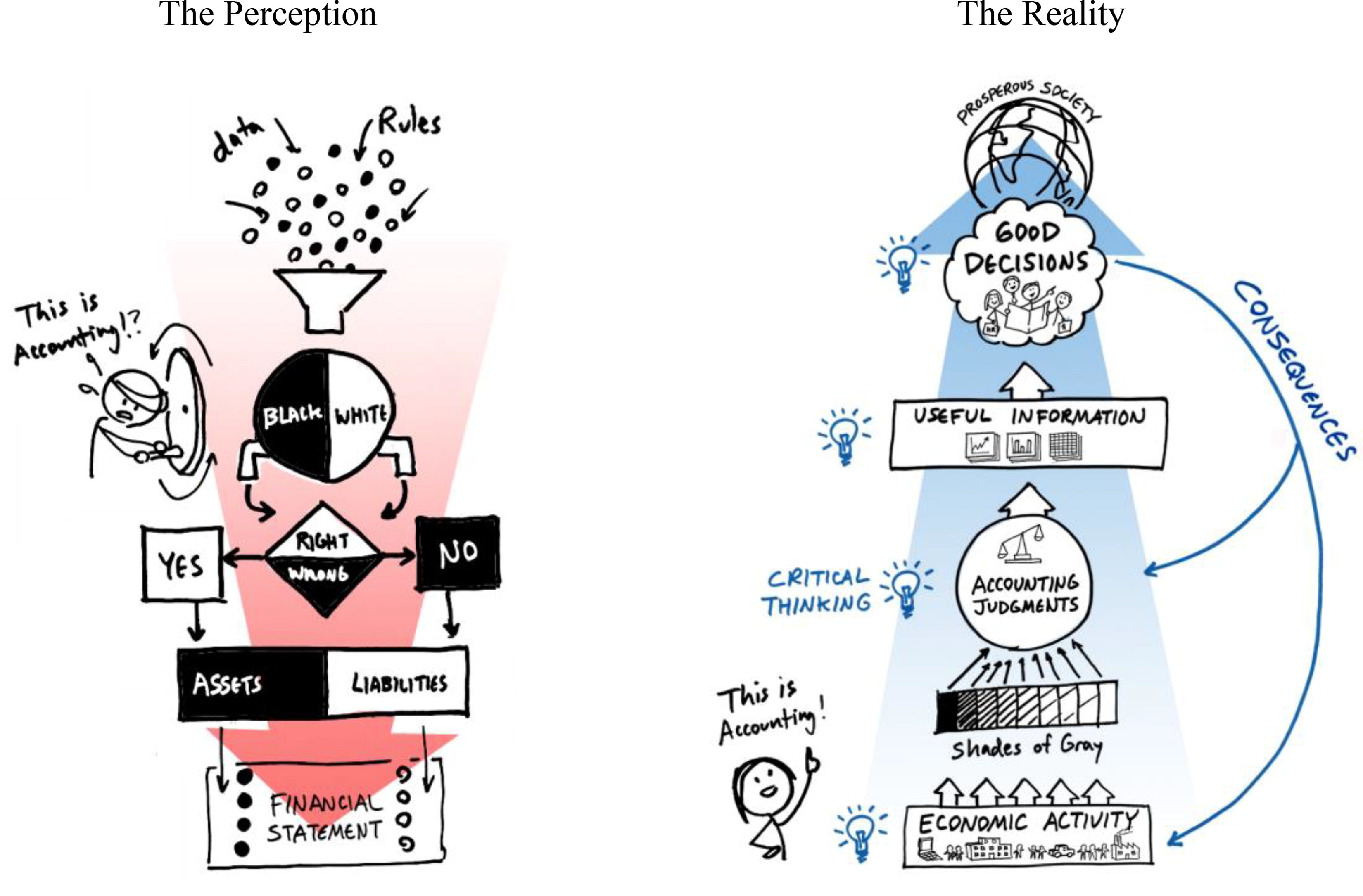

During my sabbatical, I spent some time at Stanford University. When I walked into the office of Mary Barth, professor of financial accounting and a leader in the field, she had this picture hanging in the center of her desk. She told me that she always started her first class by showing this picture. For many, accounting is the red side of the picture: accountants are bean counters. The focus is on following rules to turn data into financial statements. Accounting is usually seen as black or white, right or wrong.

In the blue side of the picture, accounting is presented very differently. Accounting is anything but bock-ticking (checking boxes). Judgment and critical thinking are essential. Accounting focuses on how businesses, governments, financial markets and society rely on information to make sound economic decisions. Investors and other stakeholders expect transparency and information about the risks companies face and how they are managed.

Mary Barth formulated her vision for the future as follows: “My vision for accounting as a learned profession by 2036 is that accounting is known as the profession that provides information for informed decision-making to support a prosperous society”.

Financial and non-financial information

To discuss accounting as a profession aiding informed decision-making for a prosperous society, we must consider both financial and non-financial information. Moreover, a necessary condition is that the financial and non-financial information must provide reliable insight into the financial and non-financial performance of a company, and this is primarily the responsibility of management.

And as we all know, this is where things sometimes go wrong and figures are manipulated, both financially (e.g. the Wirecard scandal in 2020, where the company lost €1.9 billion) and non-financially (e.g. Dieselgate or the emissions scandal in 2015). The Dieselgate scandal has raised concerns about the lack of transparency and reliability of information provided by car manufacturers on corporate sustainability.

Failures in corporate reporting can have huge economic and social consequences: not only does a lot of money go up in smoke, as in the case of Wirecard, but emissions scandals can also have a significant impact on our health and general well-being.

Three main questions

Thinking about the role of accounting for a sustainable future implies asking at least 3 key questions.

First, how do you promote useful, comparable and reliable corporate reporting?

Second, how do we integrate CSR into the corporate mindset? Because "accountants will save the world" is not just about disclosure, but also how to turn big risks into financial data points to integrate CSR into corporate thinking.

And third, what is the role of regulation?

Demand, supply and regulation

In economic terms, we have a demand for useful, comparable and reliable corporate reporting. And management is primarily responsible for supplying this information, and to increase reliability it can obtain assurance, i.e. have it audited or assured by an external party.

In addition to the economic demand for CSR information, the regulator can require that the information be provided and that it is audited. This is what the European Commission has chosen to do, but more about this later.

History

Sustainability reporting has evolved with societal values, stakeholder expectations, and regulatory requirements. While the demand for non-financial information began in the early 20th century, it gained momentum in the 1970s and 1980s. Initially, financial reporting was supplemented with social reporting, which later shifted to environmental issues.

In the late 1990s, combined social and environmental reports emerged, influenced by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Since then, stakeholder activism has driven demand for corporate sustainability, transparency and accountability.

More recently, companies have been integrating non-financial data into their strategies, driven by leaders such as BlackRock's Larry Fink. Institutional investors now recognize the impact of ESG factors on investment performance, leading to a push for international standards to guide non-financial risk disclosure.

Research

There has already been a great deal of research on voluntary sustainability reporting employing theories like legitimacy, stakeholder, agency, signaling, and institutional theory.

Some companies are motivated to voluntarily disclose more CSR information, for example, to maintain their reputation and legitimacy, to reduce political and social costs, to improve their competitive position, to enhance their brand value, or to motivate their employees.

Research has shown that a variety of global, country-specific, market-specific and company-specific factors play a role in corporate sustainability reporting.

Research also shows that companies derive benefits from voluntary sustainability reporting, such as reduced information asymmetry, improved reputation, better stakeholder management, reduced financial risk, cheaper and better access to capital, improved financial performance and increased shareholder value.

I was one of the first to study voluntary non-financial reporting in an international context (Vanstraelen, Zarzeski and Robb, 2003). This happened quite by chance when I met someone at a conference in Chicago who was looking for a co-author who spoke several European languages. So, I became involved in a study of the extent to which European companies were disclosing non-financial information, based on a list of non-financial information items that had been compiled by a committee of the American accounting profession, the Jenkins Committee, based on user requests. These items included both historical and forward-looking information.

We looked at three European countries (the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany) and found that by the late 1990s, the Netherlands was already the most advanced in reporting forward-looking non-financial information (e.g., describing favorable or unfavorable conditions that may affect the company's future cash flows). Larger companies and companies with international operations also reported more non-financial information (both historical and forward-looking). In addition, our results showed that companies that voluntarily disclose more of the required forward-looking non-financial information items have less variance and greater accuracy in financial analysts' earnings forecasts.

Yet voluntary disclosure of non-financial information and sustainability reports are not without problems. First, there is the problem of self-selection. Since companies voluntarily produce sustainability reports, establishing causal links to the benefits they gain is challenging, and we lack information on the sustainability performance of non-reporting companies. Second, there is the problem of comparability. After all, there are big differences between companies in what and how much they report. Third, there is the problem of reliability. How do we know if companies are providing reliable information instead of greenwashing?

To increase the reliability of sustainability reporting, companies can choose for voluntary assurance. My most cited article so far was an international study on sustainability assurance (Simnett, Vanstraelen, and Chua, The Accounting Review, 2009). Our results support the argument that companies seeking to enhance the credibility of their reports and build their corporate reputation are more likely to have their sustainability reports assured, regardless of whether this is done by someone within or outside the accounting profession. We also found that companies operating in stakeholder-focused countries are more likely to choose someone within the accounting profession for assurance.

EU regulation

Meanwhile, a lot has happened and in the past decade we have seen increased regulation on sustainability reporting.

Europe is leading the way here in making sustainability reporting mandatory, and it is part of the European Green Deal in which Europe's ambition is to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050.

Europe first came up with the NFRD directive: the non-financial reporting directive which was announced in 2014 and came into force in 2017. Fiechter, Hitz and Lehman (Journal of Accounting Research, 2022) investigated the real effects of the NFRD. Their research shows that companies are responding to the directive by expanding their CSR activities and are starting to do so even before the directive comes into force. These real effects are concentrated among firms that are plausibly more affected by the directive, i.e. firms with previously low levels of both CSR reporting and CSR activities. Using several alternative outcome variables (e.g., new CSR initiatives, improvements in CSR infrastructure, or firm performance), they show that these real effects reflect a meaningful increase in CSR beyond firms' potential attempts to "greenwash" their CSR performance.

Since 2023, the NFRD has been replaced by the CSRD, the corporate sustainability reporting directive. The CSRD aims to promote the publication of comparable and reliable sustainability information to help stakeholders (better) assess companies' sustainability performance and is seen as a prerequisite for "redirecting capital flows towards sustainable investments" (CSRD, L 322/16) and "helping to channel financial resources towards companies and economic activities that solve, rather than exacerbate, social and environmental problems" (CSRD, L 322/19). The CSRD recognizes "the growing number of investment products designed to pursue sustainability goals" and argues that "good sustainability reporting improves companies' access to capital" (CSRD, L 322/18).

How effective is transparency?

The focus of the CSRD is to increase transparency in a comparable and reliable manner. But how effective is transparency?

Christian Leuz, Professor of Accounting & Finance at the University of Chicago and Honorary Doctor of Maastricht University, recently gave a lecture on this topic: "How can we use transparency for a better society?

Openness and transparency are often presented as solutions to social and environmental problems; after all, sunlight is said to be the best disinfectant. His presentation focused on the role and effectiveness of transparency regimes that target specific business activities by shining a light on them. Such regimes have become commonplace for consumer protection, food safety, health care, campaign contributions, conflicts of interest, and more.

But do they work? Or are transparency regimes simply better politics than direct regulation of business activities? And in particular, does transparency work as a policy tool for social and environmental problems? Let's take a look at some of his recent research.

Christian Leuz has investigated whether transparency in fracking practices can reduce the negative environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing. The practice of hydraulic fracturing has brought significant economic benefits to the United States and increased energy security, but it has also sparked a fierce debate about safety and environmental impacts.

When Leuz and his team investigated the environmental effects of fracking, they found evidence of harmful increases in the concentration of salts from fracking fluids. This led to a study published in Science in 2021. This was the first study to show the widespread impact of hydraulic fracking on U.S. surface waters.

More recently, they found significant reductions in concentrations after states implemented disclosure requirements. Specifically, they found that companies that experienced more public pressure as a result of the disclosure mandate saw greater improvements. They concluded that targeted transparency works when it mobilizes public pressure.

Recently, they provided a first glimpse of what we can learn about the climate damage caused by each company's carbon emissions, based on one of the largest global datasets of more than 15,000 companies (Greenstone, Leuz, & Breuer, Science, 2023). Their key conclusion is that mandatory disclosure would reveal companies' carbon damages, and thus accurate reporting is critical for markets and climate policy.

Is more disclosure always better?

No. This is not the case if the information is not reliable, comparable or understandable, or if it leads to increased uncertainty because the disclosures cannot be interpreted unambiguously.

So, what does this mean for the potential success of the CSRD? The potential success of the CSRD lies in:

- Mandating greater transparency in a comparable and reliable manner by imposing uniform reporting standards (European Sustainability Reporting Standards) and making assurance mandatory. This will reduce information and financing frictions and thus improve the ability of companies to finance investments.

- Digital tagging of data, which will make data more accessible.

- The principle of double materiality: companies must determine their material sustainability topics which are those that have an impact on the company (financial materiality) and/or through which the company has an impact on society and/or the environment (impact materiality).

All of this will allow for public shaming and peer benchmarking.

Challenges of CSRD

At the same time, many challenges remain if the EU is to achieve the goals of the CSRD.

Some of the key challenges are:

- Are the internal processes of companies and their suppliers ready to provide hundreds of data points on their material sustainability topics?

- Are auditors ready to provide assurance?

- Do capital markets and investors know what to do with all this data?

- Will it change the way companies think? In other words, is there a business case for integrating ESG into all aspects of the business? As a study of Accetturo et al. (2024) point out, while addressing financing constraints may be necessary to achieve green investment, it is not necessarily sufficient. A second condition is that managers have internalized the (negative) externalities of their operations or that there is external pressure to invest in green technologies.

- And does the market really care about sustainability? Are we ready to move away from Milton Friedman's idea that the social responsibility of companies is to increase profits? Or will sustainability lead to better financial performance?

Conclusion

In short, accounting certainly has an important role to play in a sustainable future, but there are still many challenges to overcome before accountants can save the world as Peter Bakker predicted.

This blog is authored by Ann Vanstraelen, Full Professor of Accounting and Assurance Services at Maastricht University.

Also read

-

The project "BioBased Circular" has received a grant of €338 million in the third round of the National Growth Fund. The School of Business and Economics is represented in this project by Herman Wories, Programme Director at BISCI.

-

In 2002, Maastricht University became the first university outside the United States to The Frontiers in Service Conference. Now, after 21 years, The School of Business and Economics is proud to have once again welcomed service researchers from around the globe for this prestigious event.

-

Why do humans act the way they do? To answer this complex question, Hannes Rusch has to be a bit of everything: economist, biologist, philosopher, mathematician. He recently received a €1.5 million ERC Starting Grant to develop and empirically validate an interdisciplinary theoretical framework for...