Palliative care in times of the coronavirus

In the Netherlands, the chances of survival of COVID-19 patients in Intensive Care are still difficult to determine. So far, more than 10% have died, but doctors estimate that this percentage will eventually be around 30-40%. You may wonder whether ICUs therefore would become an expensive, undesirable form of palliative care—undesirable because dying alone has a huge impact. Isn’t it better to focus on providing more and better palliative care, so that vulnerable elderly people can die in a humane setting and ICU beds can be reserved for ‘those who are most likely to survive’? Marieke van den Beuken, endowed professor of Palliative Medicine clarifies the situation.

Information about the disabling effects of a long stay in the ICU, possibly in a coma on a ventilator, is seeping into the news more and more. As a result, some elderly people wonder whether they would even want to be admitted to an ICU if it came to that. Prof. Marieke van den Beuken, MD: “It has slowly been becoming clear that lying in an ICU bed with this disease is a top-level sport. Now that the first patients are leaving the ICU after a long stay, this doesn’t seem to be an exaggeration.”

Placing someone in the ICU on a respirator only makes sense if there is a chance of recovery. This can be read in the ‘Gesprekshulp behandelgrenzen’ [Information guide for treatment limitations] by Patient+, the doctors' organisation that wants to promote 'shared decision making'. But is that perhaps still difficult to assess with COVID-19?

“Yes, because there is always a grey area. If you look at vitality, on one side of the spectrum you have the professional athlete and on the other side the one who can barely walk around the house. Somewhere in between is a grey area, without hard cut-offs. There are categories of patients with whom you have to be very clear: ‘This is not a good treatment for you; it will only make you worse’. Because you die in the ICU asleep, without being able to say goodbye to your family. That is one of the big tragedies at the moment. But in that grey area, the patient also has a strong voice.”

Wouldn't it be better to focus more on more palliative care at home than on more ICU beds?

“I don’t think that’s the right question. Of course, we are in favour of very good palliative care, which is very difficult with this disease, by the way, but I’ll get back to that later. If we know for sure that ICU admission is pointless, people don’t get admitted to the ICU and we provide good palliative care. But if someone in the ICU does have a reasonable chance of recovery, fortunately we can give it to them as well." (text continues below picture)

Marieke van den Beuken

Prof. Marieke van den Beuken-van Everdingen, MD is the endowed professor of Palliative Medicine at UM and president of both the Palliative Care Advisory Group of the Netherlands and the Healthcare Working Group of the seven Dutch Expertise Centres. She is an internist and a member of various guideline committees, as well as a member of the Palliative Care Working Group of the Netherlands Internists Association (NIV).

This article is part of 'We're Open', a series of stories about the UM community’s many activities during the coronavirus pandemic.

Do you have any idea how many vulnerable elderly people in the Netherlands are currently in the ICU with COVID-19?

“I don’t know exactly who is where. The decisions about who is admitted are made on the basis of the triage document [see sidebox]. Within the grey area, many, many chances are offered to people. If they die, it’s no different, but they’ve taken that chance. As long as there are enough beds, they can. At the moment, it seems we’re going to make it with 2400 ICU beds. We have to hold on to that.”

What does palliative care for COVID-19 patients currently involve?

“We’re seeing that people who don’t make a turn towards recovery sometimes deteriorate and die in a very short period of time. So, we can’t offer our regular palliative care now—with good conversations and slowly building towards a farewell. That makes it very difficult. As people deteriorate, they breathe very quickly and have little oxygen in the blood, but fortunately they feel relatively little shortness of breath. We don’t understand that very well yet, but we are happy with it. These patients get morphine, which makes them feel less short of breath. And if they deteriorate further, we apply palliative sedation, so people are put into a light or deeper sleep.”

What did you mean earlier by the ‘difficult aspect’ of palliative care with COVID-19?

“On the one hand, our knowledge about this virus is still developing, so physically we only have morphine and palliative sedation to offer patients for symptom control. But palliative care has three components in addition to the physical: psychological, social and existential. We have a very well-run psychosocial team at the hospital, with clinical psychologists, social workers and chaplains. They are not only available for patients and their loved ones, but also for staff members. Healthcare workers are not quick to ask for help and can sometimes find it difficult to judge when they’ve reached their limits. So, the team members actively seek out the employees. Nurses who normally work with orthopaedic patients now work in COVID-19 nursing wards and are watching people die. How do you deal with that? In addition, a helpline has been set up in this region by the spiritual counsellors of the Centrum voor Levensvragen [Centre for Life Questions], where anyone can call in to talk [088-4598110]. In this way, the psychosocial and existential side of healthcare is arranged to the best extent possible.”

You're an internist yourself. Are you also at the bedside of COVID-19 patients?

“So far, no. I’m particularly busy developing new, nationwide protocols for palliative care for when there’s a shortage of people, resources and materials. In times of crisis, you don’t suddenly have to do everything differently, but we are afraid that there will be shortages and then perhaps things will have to change. A group was instantly created from the Palliative Care Expertise Centres, of which we are only one, together with numerous healthcare and expert organisations. Together, we very quickly wrote guidelines for the most important symptoms of COVID-19. What if we no longer have home healthcare, no more pumps, or medication is no longer in stock?”

The reason for this story

Last week in the news, a clinical specialist in geriatric medicine called on doctors to be cautious in referring elderly, vulnerable patients to the hospital. They would have little to gain from hospitalisation and more to lose—the prospect of a dignified goodbye with their loved ones. Anyone who is under the impression that doctors put every elderly person with serious COVID-19 symptoms in the ICU would do well, however, to read the guidelines on this issue from the Dutch Federation of Medical Specialists. Their document 'Triage at home versus referral to hospital in elderly patients with (suspected) COVID-19’ (in Dutch) describes how professionals should handle these patients: how they can best assess their chances of a good recovery. The aim of the guidelines is to prevent the under-treatment of vital elderly people, or also the over-treatment of vulnerable elderly people.

‘Very quickly’, you say, but drawing up and implementing protocols is always a lengthy process, isn't it?

“Indeed, normally that can be an endless process, but now change is happening very fast and the cooperation of scientific associations—the KNMG, the IKNL/PZNL and others—is also super, so protocols can be published quickly on their websites. This way, we can use the same approach across the board, from general practitioners to home healthcare workers, hospitals and geriatric medicine specialists.”

Could you give me an example?

“Imagine that someone is at home and there are very few home healthcare workers available anymore, but someone has to be injected with painkillers. What do we think is responsible for a family member to do? And how should you arrange that, so that home healthcare workers would have to come to the home as little as possible? We have drawn up guidelines for this, which have also been quickly approved by the Dutch Health and Youth Care and Inspectorate. It’s wonderful, how this is going. This allows us to relieve the physical distress of patients if necessary, no matter what happens.”

And the spiritual distress of the bereaved?

“I think that’s one of the biggest concerns. Soon there will be so many people who have lost someone without being able to say goodbye. We have to pay very close attention to this. In that respect, I’m very pleased with the palliative care unit that we’ve had since this week at the healthcare facility in the MECC, because we can have a slightly more generous visitation policy there.”

What kind of patients will be admitted there?

“Patients who are not going to be resuscitated or given artificial respiration and who will not be admitted to the ICU, but who do need second-line care, will be treated at the conference centre. For people who are not as sick but who can also not be cared for at home, the Van der Valk Hotel in Urmond has been set up as a ‘first-line facility’. Both there and otherwise, there is tremendous cooperation among regional colleagues of the Zuyderland Medical Center, among others.”

And what does a more generous visitation policy entail?

“To start with, each patient is given a tablet to video call their loved ones. And in the palliative care unit, they are allowed to have a limited number of visitors, with protective measures taken to ensure safety, of course. It’s not the loving contact of touching, cuddling someone and giving them a kiss on their cheek—unfortunately, that’s not possible with this disease. But people don’t die alone and that is a very great thing. Then humanity returns a little.”

Want to know more?

The Dutch-language website www.palliaweb.nl, of the Palliative Care Netherlands (PZNL) cooperative, offers a platform for and by professionals in palliative care, but it is also publicly accessible. “It also contains examples of how you can discuss this topic with the elderly”, says Marieke van den Beuken.

Also read

-

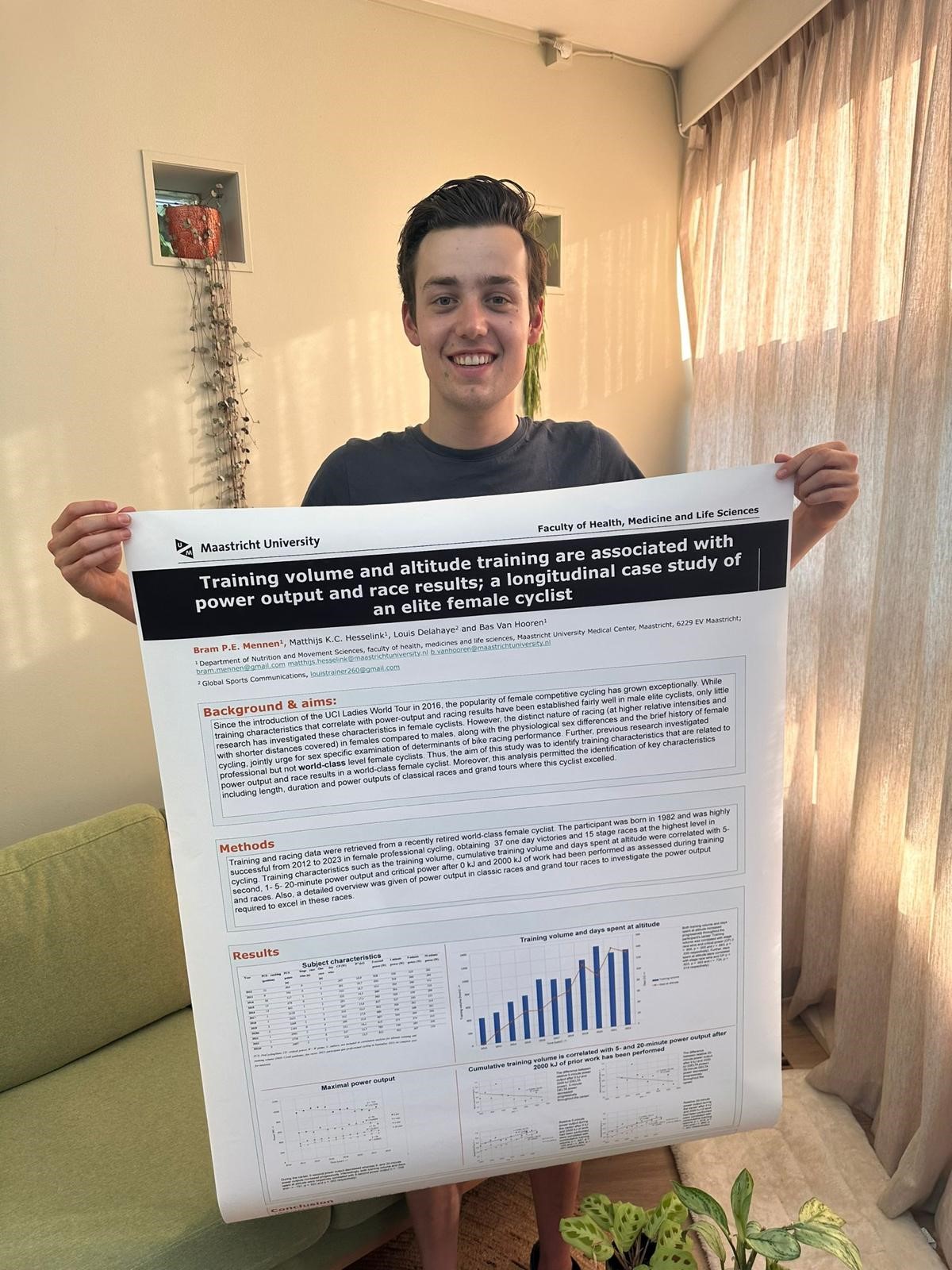

Imagine this: as a newly graduated master's student, you get to share the insights you gained during your research at an international conference. This happened to Bram Mennen. At the end of June 2024, he presented the results of his thesis on the training data of top cyclist Annemiek van Vleuten at...

-

Moving on your own to a new country with a different culture and language and without a support network can be challenging. Master's student Beverlianne Green therefore quickly realised she wanted to get involved with the local community. Through the Personal & Professional Development Portal of...

-

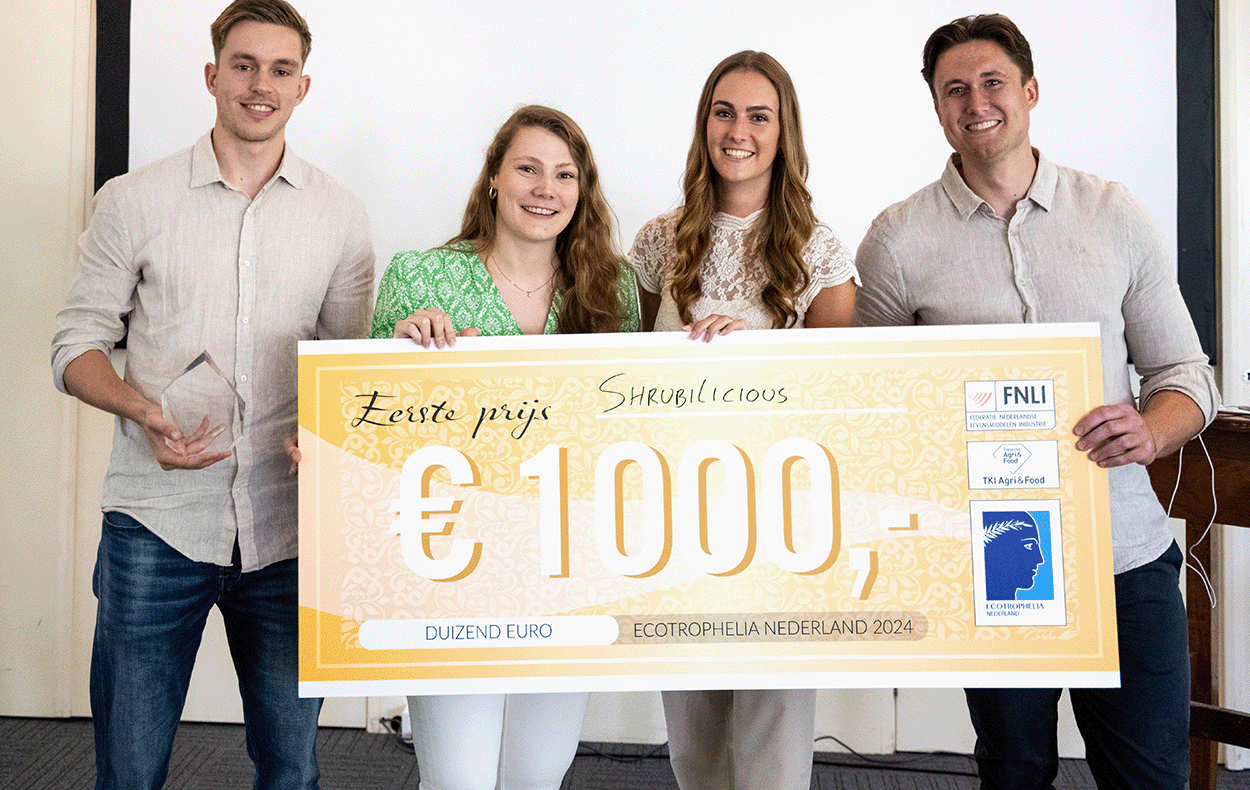

Maastricht University students have won the Dutch final of the student competition Ecotrophelia, a drinking vinegar based on apple cider vinegar, fruit and herbs.