We said, ‘Let them rot in hell’

Piet Eichholtz was one of the co-signatories of an open letter criticising the Netherlands’ reluctance to help Southern Europe in its time of need. Here, he reflects on how the coronavirus crisis is ineluctably embedded in economic, political and ethical issues.

Piet Eichholtz, Professor of Real Estate and Finance, stays home a lot and is busy redesigning his courses to get the most out of online education – like pretty much all UM teaching staff right now. But he has also caused a stir in national politics as one of the co-signatories of an open letter in one of the Netherlands’ major broadsheets, de Volkskrant.

In it, 80 prominent Dutch economists criticised the initial stance of the Netherlands – as represented by Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra – to obstruct a support package to prevent the economic collapse of the countries hit hardest by the outbreak of COVID-19. “My colleague Arnoud Boot from Amsterdam wrote the letter and sent it around to economists. Some thought that it was too harshly phrased – but I strongly support the point and was happy to sign.”

Solidarity is economically pragmatic

The Dutch economy, heavily reliant on trade and exports, is inextricably linked with the economic (and actual) health of its European neighbours. “If Italy, Spain and others collapse, there is no more market for our exports. That’s the selfish way of seeing it.” In a similar vein, the US’s “Marshall Plan” helped finance the rebuilding of post-war Western Europe – also in order to create a market for their exports.

So far, so pragmatic, but Eichholtz also objects to the framing of the argument. “The Netherlands and Germany didn’t like the instruments proposed and therefore reacted very negatively – which most people interpreted as them questioning the idea of solidarity and the principle of mutual support.” That went down badly – even at home.

Tone-deaf

The instrument in question was Eurobonds, jointly issued by the Eurozone states, which would allow economically weaker countries to borrow money at more advantageous rates – but which would also mean that the economically stronger states would ultimately be responsible for servicing the debt. The idea was first raised during the European sovereign debt crisis following the financial crisis of 2008.

“It’s like saying, ‘We have our affairs in order whereas you were not prudent enough during the good times, so why should we bail you out now that there’s a crisis?’ Put bluntly, the Netherlands told them to go rot in hell.” Eichholtz likens it to lecturing your neighbour on fire protection regulation rather than helping them save their burning house – you might have a point, but it’s probably not the best time to insist on making it…

Call it aid – or a gift

However, Eichholtz agrees with the reservations regarding Eurobonds. “It’s not palatable for the taxpayers in the North that they will have to be responsible for economic outcomes in the South.” That is why the Dutch ministers always insist on European frugality – it usually represents what their voters think. In this case, though, even the fiscally conservative taxpayer blocks didn’t approve.

How to proceed then if not with Eurobonds? “There is an emergency fund, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) with more than €400 billion in it. The richer countries should contribute to it and it should go to the countries needing it most – call it aid, or a gift, or just solidarity.” That moral point is important to Eichholtz and he hopes that something good will come from this.

Crises are the true tests of relationships

“We’ve let Italy and Greece down badly during the immigration crisis – to say ‘your shores, your problem’ is a scandal. I really hope we can extend our solidarity beyond the coronavirus crisis.” Whether the ‘European family’ is real or just a euphemism for commercial opportunity reveals itself in crises like these.

Eichholtz is aware that the Netherlands’ reaction came across as cruel. “It was not great for our reputation but I think things will move in the right direction now.” The problem needs to be solved though – epidemiologically and economically. The Netherlands had initially insisted that the deployment of the ESM emergency fund be tied to far-reaching economic reform in Italy – the type of austerity that many Italian politicians fear might hit the country harder than COVID-19 itself.

Now, EU finance ministers have approved €240 billion in loans for the hardest-hit countries, so long as the funds are spent exclusively on health-related programmes. The Netherlands were successful in preventing the issue of Eurobonds, which are still favoured by Southern European politicians and hundreds of economists in a recent open letter in the Financial Times.

“I think the outcome is satisfactory and pragmatic. Meaningful amounts of money will flow to the countries that need it most in their recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, while countries that don’t need aid will fend for themselves. The strings that would normally be attached to this aid package are loosened.”

Piet Eichholtz is Professor of Real Estate Finance at the School of Business and Economics

This article is part of 'We're Open', a series of stories about the UM community’s many activities during the coronavirus pandemic.

Also read

-

The area on the Sorbonnelaan in the Maastricht neighbourhood of Randwyck looked somewhat bare and remote about two years ago. This was mainly due to the modular and temporary appearance of the student houses that were quickly built there. Meanwhile, the area is increasingly taking on the character...

-

Two Law PhD candidates of the Maastricht Faculty received awards for their doctoral theses during the 21st International Congress of the International Association of the Penal Law in Paris.

-

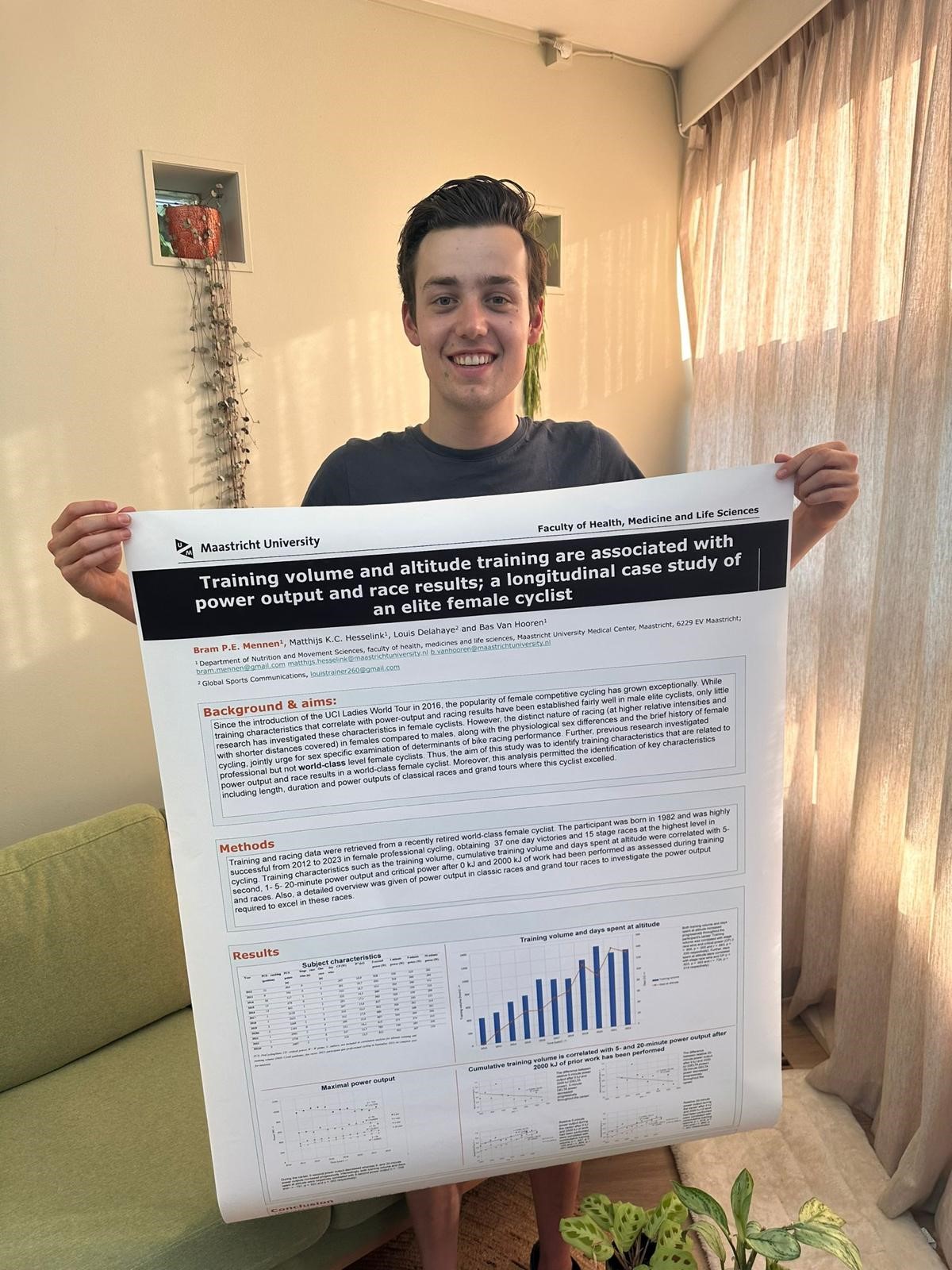

Imagine this: as a newly graduated master's student, you get to share the insights you gained during your research at an international conference. This happened to Bram Mennen. At the end of June 2024, he presented the results of his thesis on the training data of top cyclist Annemiek van Vleuten at...