Lending in the rain? How banks shape our resilience to extreme weather events

Extreme weather events have disastrous consequences for the livelihoods, health, and economic well-being of our communities. The banking sector can be an important lever to enhance our resilience. The thing is, we might have to trade off efficiency versus resilience.

Vinzenz Peters (V.)

Promovendus

Macro, International & Labour Economics

School of Business and Economics

vinzenz.peters@maastrichtuniversity.nl

Linkedin

Twitter

We are getting better at dealing with disasters… and worse

According to a recent report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), a weather-, climate-, or water-related disaster occurred on average every day over the past 50 years. The good news is that while the global number of disasters has increased by a factor of five over this period, the number of deaths has decreased by a factor of three – primarily thanks to improved early warning systems and coordinated disaster management. The bad news, again, is that the economic losses have increased sevenfold, and recent years have continued to be the most damaging ones on record. Estimated losses – $4.3 trillion between 1970 and 2021 according to the WMO – do not only comprise direct damages to physical assets and infrastructures but also business disruptions and employment losses.

Finance for Resilience!?

In light of these numbers, the concept of economic resilience has received increasing attention as an indispensable trait for individuals, businesses, and nations alike. In our context, it refers to an economy’s ability to minimize welfare losses conditional on the physical intensity of an event. Resilience goes beyond mere survival; it encompasses the capacity to adapt, innovate, and thrive in the face of adversity.

Central banks and financial regulators increasingly demonstrate their concerns about climate change and resilience. This shows the development of climate stress tests for the banking sector or the initiation of the Global Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS).

The debates on the role of the banking sector, however, are too often limited to a discussion of the risks associated with transitioning toward low-carbon economies. These discussions tend to overlook that – even under the most ambitious transition policies – some climate change is already inevitably underway. Dealing with both the transition and physical risks of climate change stresses the need to have – or build – resilient economic systems. A resilient banking system is a precondition for this.

So, how do extreme weather events impact banks themselves?

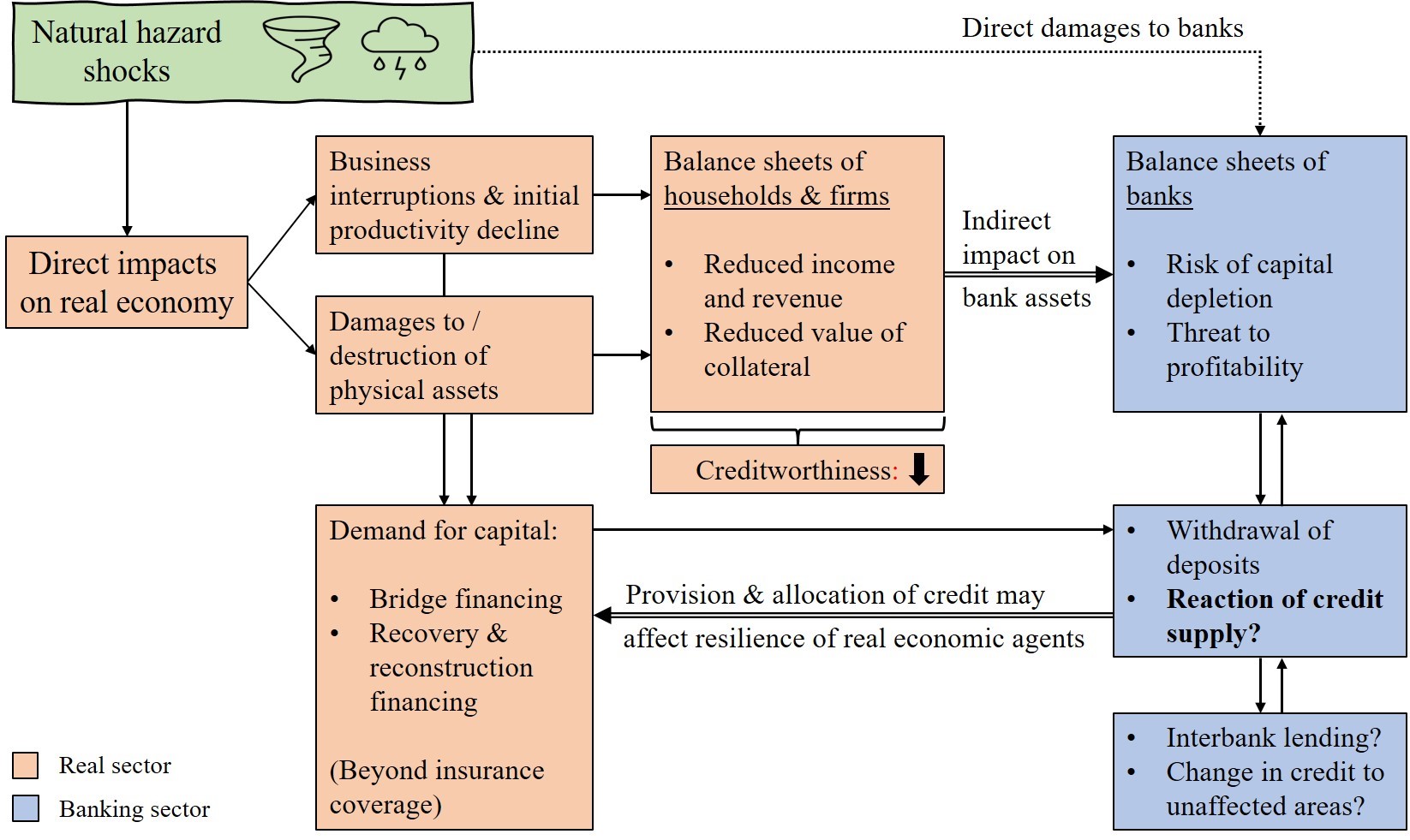

Extreme weather events and climate-related disasters directly affect banks in a number of ways. Firstly, through the destruction of physical capital. This includes both banks’ own assets as well as – and in quantitative terms more importantly – the assets of banks’ customers, such as households and firms. For the latter, the destruction of capital may lead to a reduction in their wealth, their collateral, and their creditworthiness. Secondly, the interruption of business and general economic activity in the aftermath of extreme events may further entail a reduction in income, which can lead to illiquidity, solvency straits, and borrowers’ inability to service existing debt. Banks’ customers draw down their deposits, and credit demand increases as households and firms seek to finance repair and recovery. All of this can pose serious threats to bank stability and profitability. But…

How did this play out in the past?

The good news first: In the context of developed economies, the bank-level stability and profitability effects of natural hazard shocks are significant but typically transitory. Single events have not posed crucial threats to system-level stability in the past. An important lever to increase banks’ resilience to such shocks is ensuring adequate bank capitalization. Then, credit supply tends to match post-event spikes in credit demand.

In developing economies, however, severe shocks tend to increase long-term financial risks in the banking sector, and oftentimes impair the stability of banks and micro-financial institutions for a considerable amount of time. Consequently, lenders struggle to provide credit in the aftermath of shocks, causing concerns about the feasibility of sustainable development as climate change intensifies. This is consistent with the broadly accepted conclusion that having a more developed financial sector, generally speaking, is conducive to economic resilience, as it is for economic development.

Digging deeper: Which banks lend when it rains?

So far, it has become clear that having access to financial resources through banks presents an important means for affected communities to deal with the economic consequences of extreme weather shocks. Although governments and insurances typically cover a fraction of the associated costs, banks can help by providing the necessary funds to close the remaining gap.

However: Not all banks are created equal. Banks differ in terms of both their ability and their willingness to provide recovery funds in the aftermath of a shock. Untangling this heterogeneity – Which banks might be more conducive to resilience, and why? – is at the heart of recent research.

It turns out that we seem to be facing a trade-off between efficiency and resilience. A banking sector that exhibits features often considered inefficient in “normal” times has been found to be the most conducive to resilience across a wide array of studies. For instance:

- Better-capitalized banks are better able to absorb shocks, continue lending, and thus enhance the resilience of the real economy in the face of shocks.

- Regions with less competitive banking markets recover faster. Under perfect competition, the increased risk in the local banking market implies higher interest rates. Banks with more market power can absorb the additional credit risk and continue lending without raising interest rates, because of their higher profitability. Research from the US suggests that this enhances local economic resilience to disastrous events.

- Regions with a higher share of small, locally oriented, and relationship-based banks recover faster. Such banks are frequently regarded as less efficient, and they are losing market shares to big, nationally active banks that rely on automated credit allocation decisions and are more cost-efficient. In the aftermath of extreme weather events, asymmetric information problems are exacerbated. This means, that banks have a harder time assessing whether a certain borrower is good or bad, just by looking at the “hard” information that is available. Furthermore, as collateral is damaged or destroyed, it cannot be used to secure new loans. In these situations, bankers who know their customers well are better able to extend the right amount of credit to the right borrowers. They can base their credit decision on a long mutual relationship and personal experiences and are able to assess the situation on the ground first-hand because of their local presence. Evidence from the US and Germany confirms this notion. Further evidence from Germany hints at additional benefits if these small banks are part of a group or network of banks, allowing for additional risk sharing while maintaining the benefits of being local.

- Lastly, state-owned banks represent a means to enhance economic resilience, following the simple logic that they are a potential instrument of government intervention and, through the backing of the state, usually have deep pockets to draw from. This has been shown to enhance economic resilience, especially in the case of China.

What do we learn from this?

Banks have an important role to play in helping us cope with and become more resilient towards extreme weather events. Past trends of streamlining banking systems toward more efficiency, centralization, and bigger banks may come at the cost of forsaking resilience. That is, not necessarily the resilience of the banks themselves, but the contribution they make to the resilience of our economies and, consequently, our communities and livelihoods. Striking the right balance between efficiency and resilience is by no means an easy task and there is – quite obviously – no universal way of solving this trade-off, as every country’s banking system is unique.

But it is and will be more important than ever to critically assess and openly reflect on what our future banking systems will look like and what contribution they can make to preserving and developing the prosperity of our societies. In the face of extreme weather events, we need banking systems that also lend when it rains, and not only at times when the sun is shining.

Also read

-

As a toddler, Pieter du Plessis couldn’t stay away from the kitchen. He later entertained the idea of becoming a chef—until his dream faltered under the harsh light of reality. Now a PhD candidate at Maastricht University, he uses national dishes as a lens to examine South Africa’s past and identity...

-

A study conducted by the Easo led by Prof. Gijs Goossens of Maastricht UMC+ and Dr. Luca Busetto published today in Nature Medicine.

-

Maastricht University takes care of many distinctive buildings and art works that we all know. By giving them a new purpose, we preserve these icons and give them a new meaning, making them the vibrant heart of a bustling city.

Did you know that these buildings and art works also provide access to...