Intestinal bacteria have little effect on human metabolism

Drastic changes to the bacterial make-up of the gastrointestinal system caused by the administration of antibiotics have no clear-cut effect on the metabolism of the human body. Intestinal bacteria also appear to play a much less significant role in the development of obesity and other metabolic diseases than much previous research has suggested. Scientists at Maastricht UMC+ and Maastricht University reached these conclusions after an extensive study among almost 60 overweight men. The results were published yesterday in the leading scientific journal Cell Metabolism.

Research into the billions of bacteria in the gastrointestinal system, also called the microbiome, is currently a hot topic in the scientific world. Various studies have attested that this minuscule life plays an important role in the development of obesity, type 2 diabetes and other diseases. Bacteria can break down nutrients that would normally be indigestible, for example, and the products of this action were thought to influence various processes in the body. However, little research has been done into these effects in humans in order to actually verify these assumptions.

Bile and fatty acids

In order to determine the influence of the microbiome on metabolism, 57 obese men received a course of antibiotics or a placebo)for one week. Administration of the drug vancomycin resulted in disruption of the bacterial make-up of the gastrointestinal system. As a result, the production of bile acids and short-chain fatty acids declined. Both are produced by various types of bacteria, and both are assumed to offer protection against metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. In spite of the reduction in both types of acid, however, it appeared that almost nothing changed in the metabolism of the study participants.

Risk factors

There are various metabolic processes that, if disrupted, can lead to metabolic disorders, such as the development of insulin resistance, disruptions in energy metabolism, inflammatory factors and permeability of the intestines. However, these (and several other factors) all remained unchanged after the disruption of microbial life in the gastrointestinal tract when compared to the people who received a placebo. Even eight weeks after ending of the course of antibiotics, the bacterial make-up was still changed, yet no appreciable changes in metabolism were measured. ‘It’s a remarkable finding’, says Dr Ellen Blaak, professor of Fat Metabolism Physiology.

A key that doesn’t fit

As Blaak explains, ‘Many research studies suggest that the microbiome may offer the key to tackling obesity and the prevention of type 2 diabetes, for example. However, most of these are studies have not been performed on human subjects. We have now been able to show that drastic changes to intestinal bacteria in fact do not have any clinically relevant effects. This means that in future we may have to completely change our understanding on the microbiome’s influence on our metabolism.’

This was a joint study by researchers at Wageningen University, the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam and the University of Copenhagen, conducted at the Top Institute for Food and Nutrition (TIFN), a public-private partnership between the scientific community and the food industry.

This is a press release of the Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum (MUMC+).

For more information, see: www.mumc.nl/en.

Also read

-

The Maastricht Study specialises in conducting microcirculation measurements

-

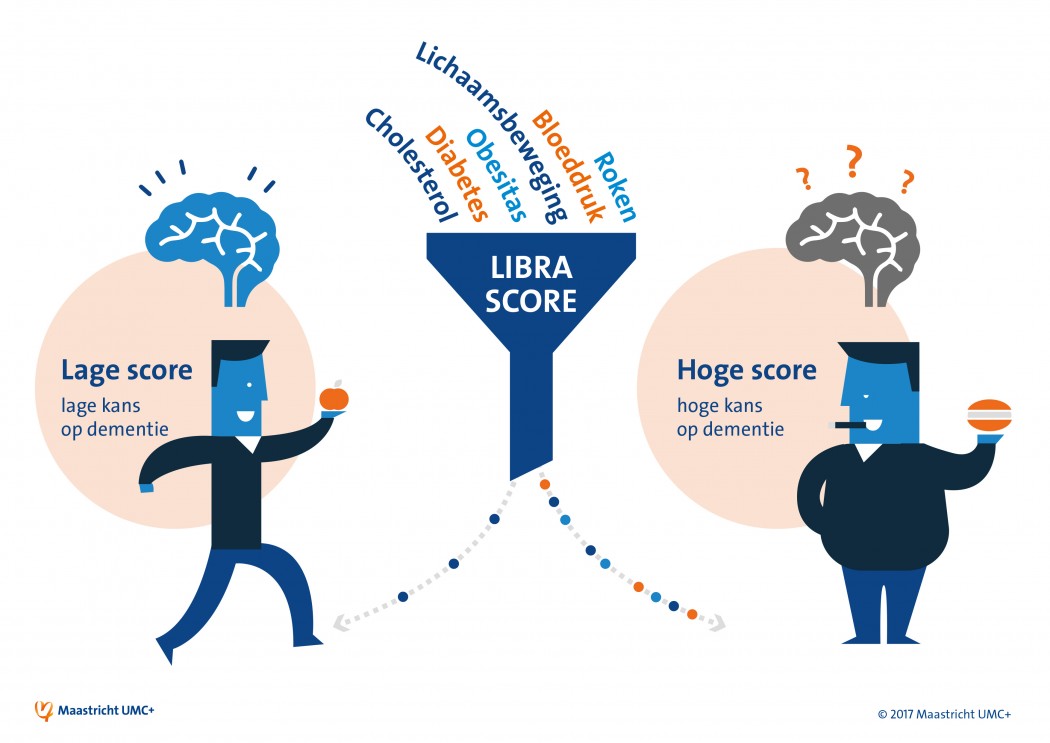

Prevention of dementia potentially stimulated by drawing up personal risk profile (MUMC+ news).

-

Less invasive operation, maximum vertebral growth, and no stray metal particles (MUMC+ news).