Invest like a Pro

How private portfolios can benefit from what professional investment managers do

Speculators are not the real investment stars

Not to put all your eggs into one basket is probably the one portfolio theory that has made it into mainstream wisdom about investments. But what does this really mean when you look into your portfolio and how do the world’s big asset owners translate this into their investment decision making?

It is often the speculators, like George Soros, or the Hedge Fund bosses, with that one daring and successful bet, that are considered famous investors.

Consider, for instance, how Soros bet against the British Pound in the 1990s which has made him a cited star investor with a single trade. Or also: Bill Gross, who was known as the Bond King for his successful Total Return Fund until markets, his own style, and the less than stellar performance forced him out of the company (PIMCO), which he had made big.

But these stars are typically people specializing in the trading within an asset class or based on a limited set of trading strategies, but can rarely be called investment managers. The latter are responsible for managing the overall portfolios of big asset owners, such as insurance companies, pension funds or sovereign wealth funds. It is this group of people that decides how much of a portfolio to invest where and with these decisions is responsible for the investment outcomes.

The next few paragraphs shall highlight what investment managers do to achieve the outcomes needed by pensioners or beneficiaries of endowments, and where a more institutionalized approach to investments can help the private portfolio.

Investment managers follow an institutionalized process

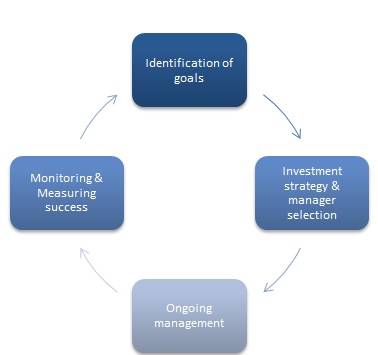

Figure 1 shows the four key elements in the investment management process that all investment managers of large portfolios follow in one way or another.

As a first step it is vital to develop and understand the targets that the investments are meant to serve. Targets can come in multiple facets, but eventually can be boiled down to one dominating factor out of the following three: (i) return target, (ii) risk tolerance, or (iii) allocation preference. Investment managers often define these on the basis of explicit liabilities that stand opposite of the assets (for pension funds, for instance, these are future benefit payments for plan members that are often linked to some minimum return target) or financing needs of operations / for research, as is frequently the case for endowments. Examples for targets of the latter group can be real capital preservation (i.e. after inflation) plus a distribution of, say, 2%.

Once targets have been defined and agreed upon, it is the role of the investment manager to develop an investment strategy aimed at achieving the targets with high confidence. This begins with the strategic asset allocation (i.e. the allocation of funds between various asset classes, such as fixed income, equities, and liquid (e.g. hedge funds) or illiquid alternatives (e.g. private equity or real estate)) and goes all the way to selecting appropriate asset managers to implement the allocation to a given asset class. Especially the former step is vital, as more than 90% of a portfolio’s risk and return potential is determined by the choice of the strategic allocation. Furthermore, it is for the investment manager to decide which asset manager to select and whether there is room in the portfolio for some of the alleged stars. Important criteria in this selection process are costs and the manager’s expected outperformance capabilities.

In addition to the target setting and implementation of the investment strategy, a portfolio also needs ongoing management, such as rebalancing of portfolio weights. Lastly the investment manager needs to ensure that the portfolio develops in line with expectations and that she understands performance drivers. For this purpose an appropriate monitoring of performance and risk relative to the investment targets needs to be in place, so that the investment strategy can be amended, if needed.

Bearing in mind the institutional approach to investment management also benefits the private portfolio

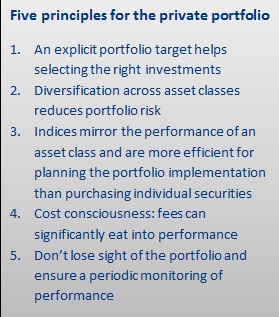

Also individuals and their portfolios can benefit from an institutionalized investment approach and eggs in many different baskets. Start with the targets that the portfolio is supposed to achieve: someone who is young and sets aside funds as old-age provision can typically afford a much riskier portfolio than the same person who is saving money for a big expenditure within the next 12 months. Making the thought process of the portfolio target more explicit helps selecting the right investments to achieve this target.

When devising the investment strategy, spreading funds over multiple asset classes offers diversification benefits and thereby reduces portfolio risk. Furthermore planning the allocation based on a representative index (e.g. the S&P 500 for US equities or the MSCI Europe for European equities) is more efficient and less risky than buying individual securities (unless one wants to implement one’s own trading strategy).

Translating the investment strategy into actual investments, individuals then need to select investment funds that mirror the performance of each chosen index. Especially for individuals, cost consciousness in selecting the appropriate funds is decisive, as costs can often significantly eat into the performance. If a fund has a front load or management fees in excess of what a passive vehicle (i.e. exchange traded fund (ETF)) would cost, it is important to evaluate whether the expected benefits of such a fund outweigh the additional costs.

Lastly, regular monitoring of the portfolio performance is important to assess whether the strategy holds up (remotely) to the target in mind. It builds the basis for strategy refinements.

Figure 2 summarizes the five key principles where an instituional approach to investment management can help individual portfolios

If one is looking for further guidance in the investment process, independent advisors can typically help to structure the target setting and translation into an appropriate strategy including funds, but bear in mind the additional cost layer. Of late, some robo advisors have started to offer a cost efficient alternative in this process.

To take away

Investment managers of institutional portfolios aim at developing investment strategies that are designed to meet specific, pre-defined, targets. All-eggs-in-one-basket strategies will not help the people in charge to achieve their goals with highest confidence. This is why they define investment strategies and strategic allocations that aim at reaping multiple risk premia and benefit from diversification. For this reason also individuals should think of their targets before investing and not implement a strategic allocation to, say, European equities by only buying the stock of a single company.

About the author

This blog was written by Dr. Christian Wiehenkamp who currently works as Chief Investment Officer at Perpetual Management GmbH.

Prior to joining Perpetual, Christian held several positions within the Allianz Group. In his latest role he was the responsible investment advisor at risklab / Allianz Global Investors for family offices and fiduciary clients. Prior to this, he worked as risk manager at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, leading the risk governance activities around the economic capital model. Christian holds a doctorate degree in Finance from Goethe University Frankfurt and obtained a Bachelor’s degree in International Business Economics (2006) as well as a Master’s degree in Econometrics (2007) from Maastricht University. In addition, he is committee member of the Alumni Circle Munich where he organises UM alumni events on a frequent basis. Christian is author of several articles on model uncertainty, option pricing and alternative illiquid asset classes.

Other blogs:

Also read

-

In this article I discuss several differences between startups and starting businesses. I find this important because over the last year, I’ve gotten increasingly frustrated about the types of questions I (as a startup founder) would get. “Can you already live from your startup?” “Why is raising...

-

As a family therapist in an ambulatory setting, I see varying psychiatric disorders in multiproblem families. I specifically work with families who not only suffer from any kind of disorders, but also are affected by mild intellectual disability. This blog encompasses two parts. First, it will give...

-

I had a lot of fun at the EU Studies Fair. For me it proved a very fruitful event for both students and professionals who are trying to get a foothold in that lions’ den that I call “Eurobubble jobs.” In my experience this can be quite a daunting challenge, but if it has been a journey that I think...