Sense and Sensibility: [Lawyer Edition]

The Harvard Professor v. The Chinese Restaurant

During the first lecture of the popular Comparative Contract Law course here at the Maastricht University Faculty of Law, MEPLI’s Jan Smits – the course coordinator – starts off by cautioning the first-year students. He states that when one commences the study of law, they will start seeing the world through “law goggles” where everything and anything we see becomes a potential legal issue: a banana is no longer just a fruit, but a tort waiting to happen, and every promise is a fundamental breach in disguise. Implied in his admonition is that as we embark on the study of law, it is important for us to maintain our sensibility and to hold on to our common sense with a kung fu grip.

The Harvard Professor v. The Chinese Restaurant

As we become more involved and intimate with the law, however, it is inevitable that some of us start to lose our grip on this notion of sensibility and reasonableness. A legal dispute that has received some viral attention highlights this point.

The dispute (which has yet to make it to court) is about a Harvard Business School professor (with a BA, JD and PhD all from Harvard) who ordered some Chinese delivery. The restaurant’s website listed an old menu (with cheaper prices), which failed to reflect the increased price on their new menu. This meant that there was a $4 discrepancy between what the professor (who ordered online) expected to pay and what the restaurant charged him. The issue between the disputing parties, in essence, is about what the Chinese restaurant should do to remedy the situation.

My first question to the dear reader is, who do you sympathize with more: the “victim” (the Harvard law professor who was “cheated” out of $4 and is now on a vigilante crusade against the restaurant) or the “accused” (the family owned Chinese restaurant that is simply trying to make ends meet, but did not have the resources necessary to keep their website constantly up to date).

If the dispute goes to court (as the professor threatens in his email), a strict textbook analysis of the case is relatively straightforward: the professor bases his damage claim on Massachusetts General Law, Section XV, Chapter 93A, Section 9, which states – in relevant parts – that a person who has been injured by another person’s unlawful action may claim damages. Because the restaurant failed to update their menu prices online, while at the same time charging the updated menu prices to its customers, this amounted to an “unlawful practice” (i.e., fraudulent practices) and the professor should be entitled to claim damages. A “sensible” solution would have been for the restaurant to reimburse the professor the $4 and for the restaurant to update their online menu, but clearly, the professor – who teaches and consults on “online fraud and advertising fraud” – felt that this particular solution was grossly inadequate.

One of the pivotal issues here has to do with the fact that the professor is seeking punitive damages from the restaurant: the professor writes in his email that the restaurant “intentionally overcharge[d] a customer, [and therefore] the business should suffer a penalty larger than the amount of the overcharge”.[1] While punitive damage (a type of damage that serves not only to punish, but deter future violations) is a doctrine more widely accepted in the United States and less so in Europe, it is difficult to justify the professor’s demand for punitive damages – that he be reimbursed $12 instead of $4 – especially when the basis of his claim is Chapter 93A. This is because Chapter 93A allows for punitive damages only after the parties have failed to settle the matter reasonably. The offer by the restaurant to pay back the difference could be argued as very reasonable solution, but the professor failed to see it as such.

The second noteworthy issue in this case is the fact that the professor is not only seeking 3 times the amount of what he was overcharged, but the fact that he reported this “violation” to the authorities “to compel [the] restaurant to identify all consumers affected and to provide refunds [plus damages] to all of them”. While I respect the professor’s Batman-like sense of justice to go to “war” with the Chinese restaurant, I cannot help to wonder whether the professor’s retaliation was proportional to the $4 damage that the restaurant inflicted upon him. Could this have been – to quote Jean Racine – an instance where extreme justice became extreme injustice? Or as an eager Latin-phile would say, a case of summum ius summa iniuria? Clearly, the restaurant messed up. There is no doubting that factual point. Where there is doubt, however, is whether compelling the Chinese restaurant to identify and locate all the consumers affected by this and not only to reimburse them, but also to pay them additional damages could be construed as a sensible/reasonable solution?

From this case, I want to extrapolate three general questions that I will briefly dive into with my remaining paragraphs: (1) is there a correlation between legal education and/or becoming a lawyer (thus putting on law goggles) and the level of their common sense?; (2) is there room for empathy in an adversarial system; and finally, (3) what role did vision science and social psychology have on how the reader judged the case and did the law goggles possibly affect our vision? Ok, so technically 4 questions, but whatever. I’m a lawyer.

Lawyers and Common Sense

Was this case above about a Harvard professor (albeit with an impeccable CV) simply losing his grip on common sense and sensibility? Or was it something more vicious[2] in that he wanted to use his knowledge of the law to teach a layman a lesson? Or did he have nothing but good intentions and simply tried to prevent future customers of the restaurant not to be overcharged?[3] The truth is likely a combination of all three, which would suggest that yes, the professor did go just a tad overboard with his full frontal retaliation for a mere $4 overcharge. The first question that I pose here is whether or not his legal education – a very esteemed one at that – contributed to his actions? In other words, did he have his law goggles on? For those of us who are more familiar with the law, when we witness instances of non-compliance, are we more likely to call people out on it at the risk of being a “douche”? In other words, are we guilty of sometimes trying to prove a point just for the sake of proving our point because we think we know better?

In the present case, we have a small family owned business – allegedly – that is simply trying to make ends meet. By all accounts given, they are hard working people and their food is “delicious” (even according to the Harvard professor). But the law, if strictly enforced, could bury this family and force the restaurant to possibly file for bankruptcy. Would the professor’s “law goggle” be to blame if this was to happen? Had he not been an expert on online fraud or fraudulent advertisement, would he have been more sensible in the way he would have approached the situation?

Empathy v. The Adversarial System

Part of being a sensible human being – at least in this author’s humble opinion – is to have the ability to be empathetic or to be able to view the situation from the perspective of the other party. The professor clearly failed to do so here, but is that his fault and his fault alone, or is that how we are training our lawyers today? In an adversarial system, especially, this notion of empathy might be just as inherently repugnant as the notion of good faith in England (to borrow Lord Ackner’s language in Walford v. Miles). So, does putting on the “law goggle” also lead to “enhanced egos”? Is there a correlation between putting on the law goggle and losing our sense and sensibility? This is not in any way to suggest that all lawyers are bad, although a plethora of lawyer jokes would suggest otherwise. However, for some reason, there is a perception that lawyers are usually Type A gunners who will never miss an opportunity to jump all over you for expressing opinions that conflict with theirs. While this might be a “successful” strategy in court, it is not the way to be a decent human being.

Vision Science, Snap Judgments, and Their Influences in Law

Related to the issue of perception and whether lawyers generally get a bad wrap, for this following paragraph, I would like the readers to pause for a second to answer the question posed at the very beginning (based only on the facts provided here, which admittedly does not portray the entire story): who do you sympathize with more, the “victim” or the “accused”?

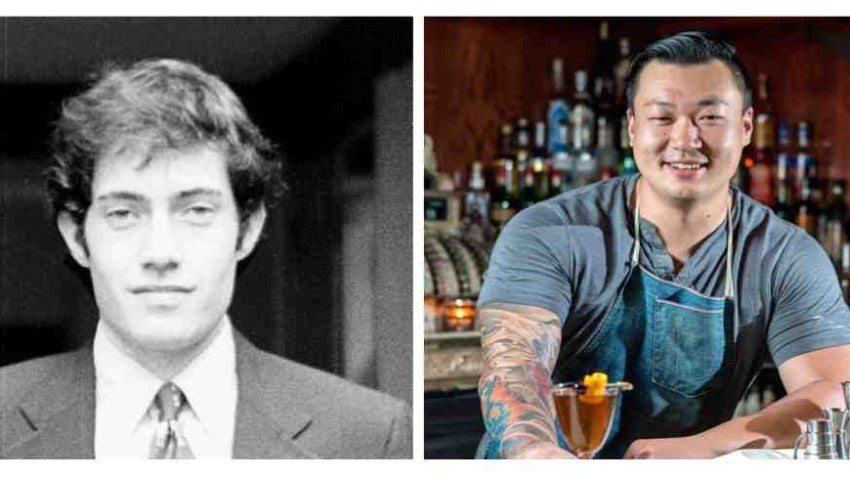

Malcolm Gladwell wrote at length about our abilities and/or tendencies for snap judgments referring to this ability as “thin-slicing”, but there is a serious academic study called “vision science”, which goes much deeper in analyzing how our perceptions and what we see through our eyes affect our subconscious: vvision science, especially in a social psychology context tells us that “visual features perceptually determine categorical thinking and have profound downstream consequences including stereotype activation.”[4] So, vision scientists would look at our present case and ask questions like to what extent did the photo of the Harvard professor (in black and white smiling awkwardly) and the Chinese restaurant owner (in color displaying his tattoo) have on our initial gut reaction (if at all)? Or from a more social-psychological perspective, a question like what impact did your race or education level have in you reaching your snap judgment? If you are Asian, a restaurant or small business owner, were you more likely to side with the Chinese restaurant owner? Or if you have studied the law or attended an Ivy League school, were you more likely to find the action taken by the Harvard professor as more sensible? And the last lingering question that I have, which I cannot answer here, is whether the effects of law goggles are real and tangible and whether the case of the Harvard professor and the Chinese restaurant, was a sad illustration of the goggle’s corruptive powers?

Conclusion

Admittedly, some of the questions posed above were rhetorical, but there were few questions, which were left unanswered simply because I did not have the answers. There is one concrete point, however, that I hope the readers take away from this if nothing else and that is to be mindful of the risks that come with studying the law or becoming a lawyer. Given that it is the holiday season and many of us will be spending time with our “laymen” family members, let us resist the urge to “lawyer” every situation. Let us not argue for the sake of arguing just because we think we “know about the law”. And let us all resist that feeling of smug superiority and thinking that just because we are lawyers that we are somehow better than others. There is a reason why there are so many lawyer jokes in this world as is[5] so let us not add to it even more. Heck, even the Harvard law professor publicly apologized admitting that he failed to act with “humility” and said those three heartwarming words, “I am sorry.” Of course, had the professor hired a lawyer he/she would probably have advised him not to apologize because that would be construed as an admission of guilt in court… but, alas. Happy Holidays!

[1] It is worth noting here that while the restaurant admits to failing to update their menu, the issue of whether there was an actual intention to deceive consumer has yet to be determined.

[2] It could also be argued that the professor also interpreted Chapter 93A in a way that suited him.

[3] To be fair to the professor, on this last point, the professor himself pointed out in his email to the restaurant that he was concerned that there were number of other consumers that could have been mislead by the advertisement of the restaurant and were subsequently overcharged.

[4] R.B. Adams Jr, N. Ambady, K. Nakaytama & S. Shimojo (eds). The Science of Social Vision (Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2010).

[5] As the lawyer awoke from surgery, he asked, "Why are all the blinds drawn?" The nurse answered, "There's a fire across the street, and we didn't want you to think you had died."